Try the world's most popular OSINT platform for free. Elevate your enterprise investigations with unmatched accuracy.

“There are many people behind the program, and I am one of them…” – A Magic Cat developer, alias ‘Lao Liu’ [Source: NRK]

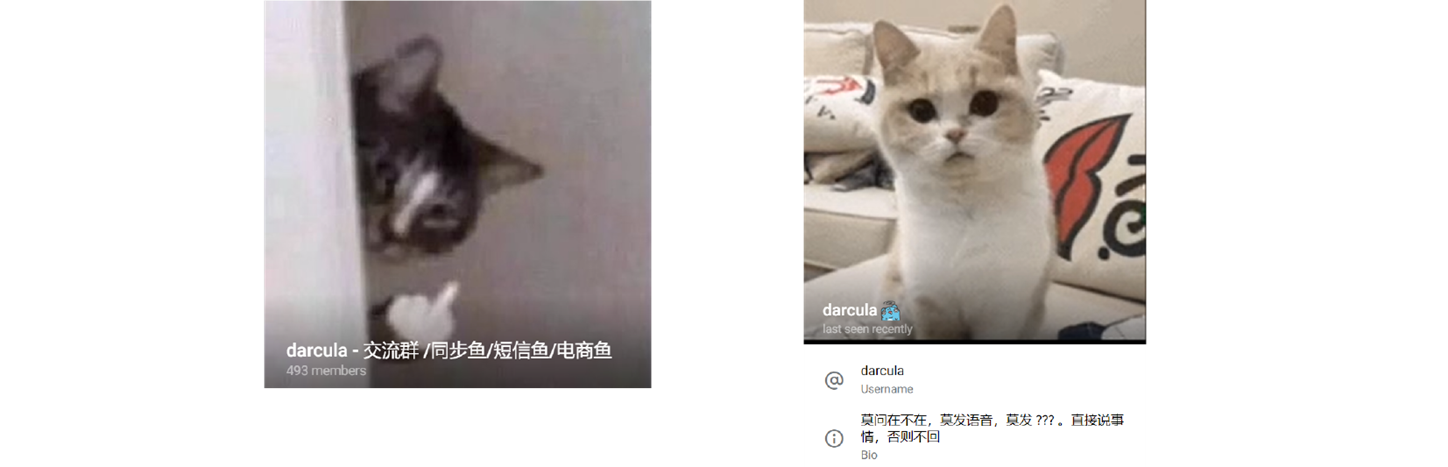

The members of the Telegram group named ‘Darcula’ communicate exclusively in Chinese. No faces, only cryptic usernames and anonymous profile pictures – mostly chibi mascots and adorable cartoon animals.

Members share images of phones, SIM cards, modems, servers, racks of devices and stacks of documents. In between, they’re advertising an impressive lifestyle. Luxury flights; a red Ferrari 488 parked beside a new Lamborghini Aventador; champagne-soaked parties in Bangkok; four box-fresh pairs of Valentino Rockstud heels; nestled on a bed of receipts, a diamond Bulgari ring shaped like a venomous snake glittering on a left index finger, list price approximately 30,000USD.

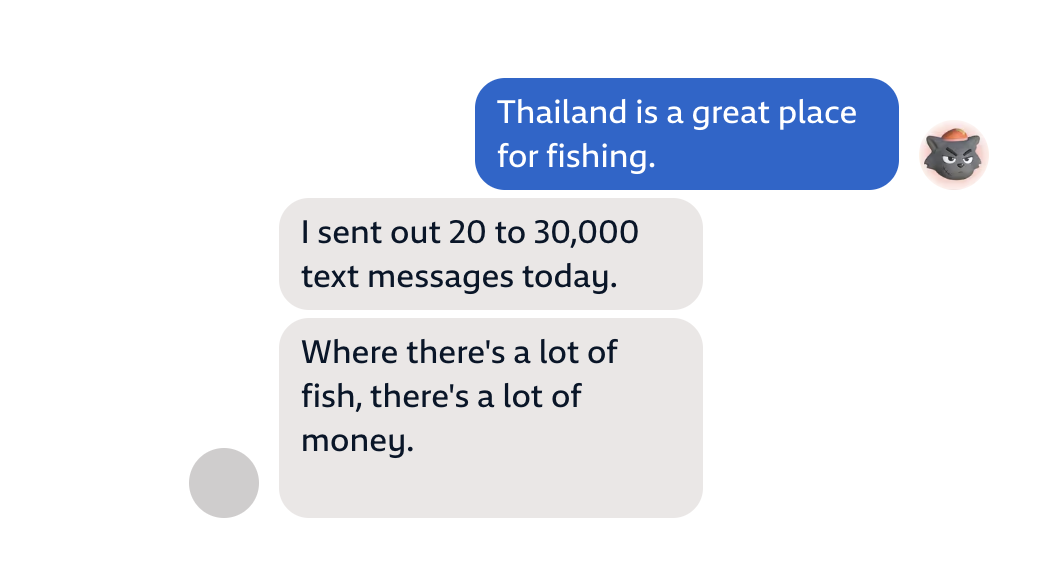

But who are the members? One of the most active users can be identified by his username: x667788x. He appears as a Chinese cartoon wolf in a little patchwork hat with a mischievous grin, and behind this playful avatar is a user with a penchant for Louis Vuitton – and ‘fishing’.

If you thought this group looks more Mafia than maritime, you’re correct. These messages don’t suggest x667788x is slinging an LV spin rod.

“The fraud categories most seen by the police in 2024 were advertisement frauds, investment frauds, and phishing - for example, message scams.” – Jon Andre Hvoslef-Eide, Acting Public Prosecutor at Norway’s Økokrim [Source: NRK]

This is phishing with a ‘ph’. The Darcula group is dedicated to luring ‘fish’, or victims, into carefully laid SMS, iMessage, text or WhatsApp traps, pre-loaded with ‘bait’: fraudulent links. Via these links, cyberscammers can harvest bank details, passwords and money from the vulnerable to fund their first-class criminal lifestyles.

What’s more, this group is one of the best. The technology ‘Darcula’ originated is the source of an estimated 70-80% of SMS phishing or ‘smishing’ scam messages. Phishing-as-a-service (PhaaS) is big business, with a bi-monthly total of a million individual attacks at the start of this year. According to American and Norwegian security researchers, alternative Russian-origin operations do exist, but none on the size and scale of their Chinese-speaking counterparts. Chinese smishing-as-a-service boasts a unique level of professionalism. Slick toolkit-led enterprises like the ‘Smishing Triad,’ ‘Lighthouse’, ‘Panda Shop’ – and, crucially, ‘Darcula’ – represent a tactical shift by smishers from isolated attacks to industrialized fraud. The Smishing Triad alone operated in 121 countries, sending up to a million scam messages over 20 days. This network of tens of thousands of phishing domains could be sustained by parasitizing China’s Tencent and Alibaba infrastructure, exporting DIY cybercrime around the world from Chinese megaservers. Subsequent kits have gone one better, refining the model to targeting banks themselves. Servers can be anywhere, with newer toolkits exploiting digital wallet systems like Apple Pay and Google Wallet. ‘Darcula’ is one of these.

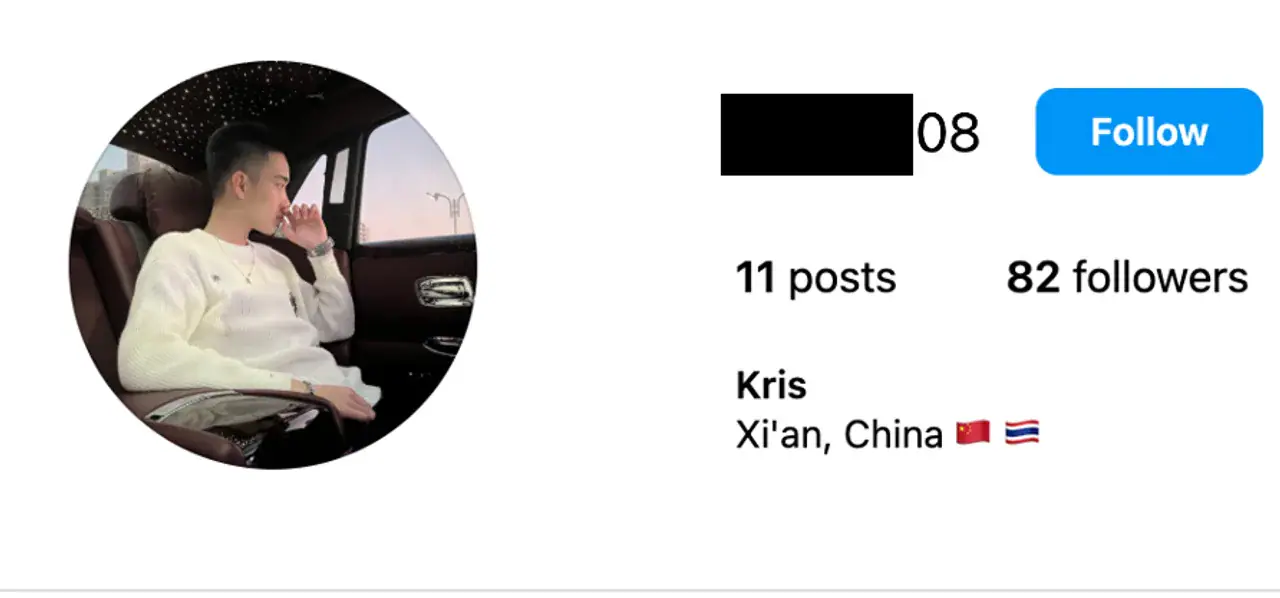

The Telegram group is just the shopfront. However, if you pinpointed details from shopping sprees, video posts and messages – like Norwegian broadcaster NRK did – you could find x667788x’s phone number, visible for a matter of seconds. You might find it registered in Thailand, matching the GeoInt data he revealed. Investigating this number with OSINT, you might find a Line account too.

Tracing x667788x’s OSINT brought NRK to the realization that cartoon wolf’s cheeky smirk hid a young Chinese man. He’s not really the man seated in a swish black car with a roof patterned like the night sky, but his name is ‘Kris’. Calling the Thai number and tracking his accomplices allowed NRK to present him with a series of questions. Namely, why and how he had collected over 10,600 bank cards with the ‘Darcula’ toolkit. Was he in charge?

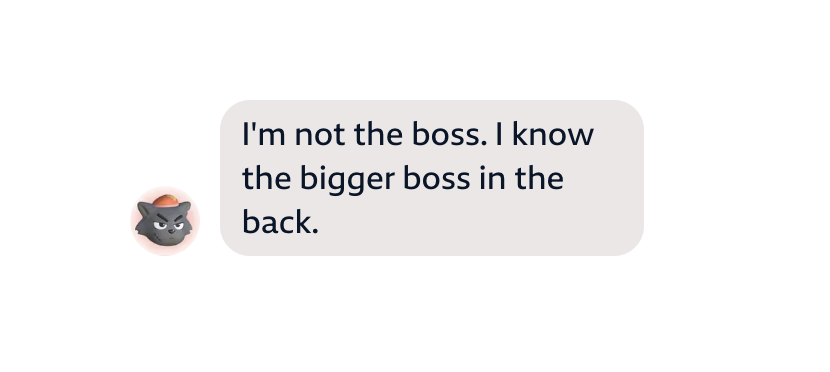

His reply brought up more questions than answers. ‘Darcula’ was not just the name of the group, but the name of a person. Darcula was the boss – a boss x66 was reluctant to discuss.

In 2023, an Israeli security expert attempting a similar investigation had uncovered this name before. In 2024, Netcraft reported Darcula had “emerged from the shadows” in a hundred-plus countries. There had been stories of a 19-year-old man, a tech company dropout after just one month on the job, a ghost on social media and the web as a whole. Within three years, this figure was behind the world’s most competent phishing program. Recent reports discuss Darcula’s software implementing generative AI so even non-technical wannabe criminals can wreak havoc in multiple languages.

An OSINT investigation was about to reveal the world’s most wanted mysterious phishing impresario. The answer, it turns out, was in the monster he made.

“Is [Yucheng C] one of the founders of Magic Cat?”

“You can publish that, it doesn't matter. The income belongs to the company; he just gets the salary.”

“Is he the creator of Magic Cat?”

“He is just one of the technologists who developed the program. (...) We don't want to lose him.” – Interview with x66/’Kris’, NRK. [Source: TV2]

Meet Harrison and Erlend, Cybersecurity Researchers.

IT security expert Erlend L. ‘had no intention of becoming a scam hunter.’ Working together at Oslo-based cybersecurity firm Mnemonic, neither did his American colleague Harrison S.

That is, until Erlend received a suspicious text.

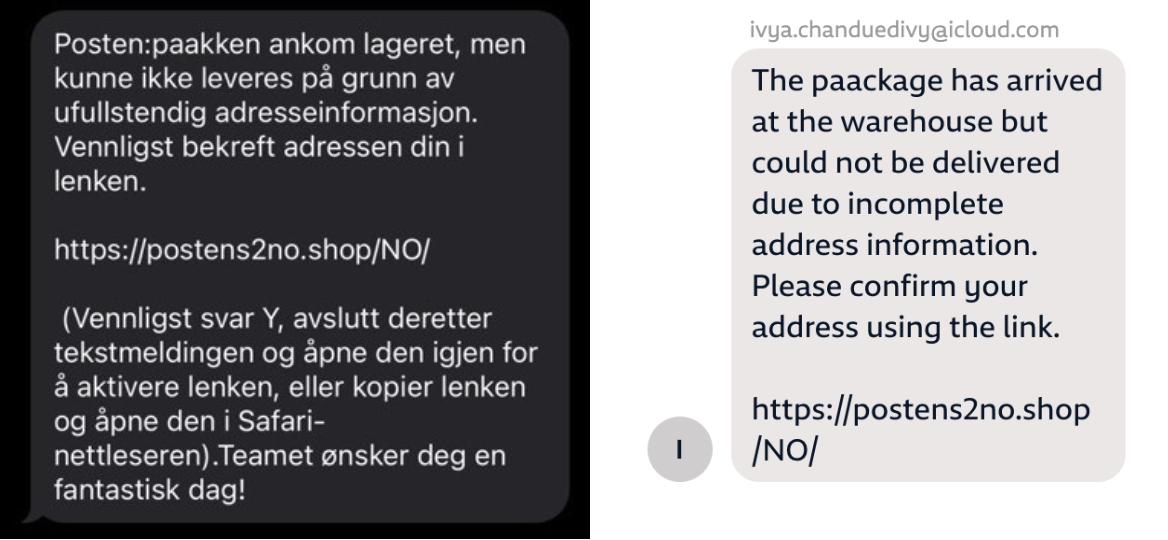

The text claimed to come from the Norwegian Postal Service, concerning ‘missing’ details on a parcel that has incurred a resulting fee. According to Harrison and Erlend, there are legitimate reasons that tolls can arise from packages sent to Norway internationally – but ‘this was not one of them’.

It was clearly suspect: badly spelled, from an unofficial iCloud address and complete with an embedded URL. In a word, it seemed scammy. A prime example of an SMS phishing or ‘smishing’ message. But it only took a Google search to show Erlend’s text was not the true beginning of the story.

News articles and social media posts indicated that since December 2023, these messages had been popping into the inboxes of not only Norwegians countrywide, but receivers across the globe. Some may have genuinely believed there were packages waiting for them at the post office when they received an SMS, iMessage or RCS message like this one. The source was not as yet clear. Mnemonic’s two researchers saw the simple advice given by the police, brands in question, impersonated banks and the security community: ‘do not click the link, delete the message.’

This, however, is not how an ethical hacker’s mind works. Harrison and Erlend’s curiosity at how this operation ticked was overwhelming. They think it was “probably this thirst for knowledge combined with our backgrounds” that influenced their reaction.

All conventional advice was pointing towards anything but doing what 138,000 Norwegians had already done – clicking the link.

Naturally, Erlend clicked it.

These researchers may have had no intention of becoming hunters, but this journey would turn them into pros. Before long, Harrison and Erlend will have developed software that cracked Darcula’s world wide open. The scammer who masterminded this message would have been monitored, unawares, for a year with the help of Norway’s NRK, exposing the nuts and bolts of China’s most sophisticated phishing scheme. Reaching out to Norway’s public broadcaster brought this investigation the kind of cross-sector attention that is the only way to cut these criminal groups off at the root. Subsequently, Harrison and Erlend reached out to OSINT Industries to describe how our tool was pivotal in finding Darcula himself. While Mnemonic’s intrepid experts focused on reverse-engineering the phishing software, OSINT Industries was key in exposing the human, putting a face to the notorious name.

Over 40,000 chat messages, hundreds of thousands of victims around the world, technical insights into a top phishing toolkit, and a glimpse into the lifestyles funded by this at-scale operation. This is how the scam works.

“Early on in the project we made a conscious decision to focus on the big picture…. Most of the work up until then had been technical in nature, focusing on the latest software they used... We knew that the most likely outcome of repeating that type of work would be the group learning from their mistakes, and us driving them further underground… To address and counteract the issue of smishing, phishing, and scams in general requires attention from different sections of society. Financial institutions, mobile network operators, big tech, law enforcement agencies, and the general public all have their part to play. – Erlend L. and Harrison S., Cybersecurity Researchers [Source: Mnemonic]

The Admin Room: Hacking the Hackers' Toolkit

Clicking the link gave Harrison and Erlend “more or less what we expected” on their smartphone screen.

They had been redirected to what claimed to be an official Postal Service page, and another button to click. A form allowed respondents to input their address details as well. More ammunition for the scammers, it seemed. When this information was provided, a chain of further pages led to a request for payment: a surefire way to harvest credit card information. For a smisher, this would be the cherry on top.

Harrison and Erlend were eager to start digital forensics, but were quickly faced with a hurdle. An ordinary laptop computer – not a smartphone or tablet – is one of the key tools of a security expert’s trade. However, making an attempt to open the smishing page on a desktop computer was impossible. Several anti-forensics features limited access to only cellular devices, and only cellular networks. This meant security features couldn’t inspect the link for malicious content; these domains and messages couldn’t be flagged or taken down for what they are – phishing attempts.

Mnemonic’s researchers started with a man-in-the-middle proxy tool. By changing the User-Agent header to match that on a cell phone, they could maybe bypass the smishers’ defenses. Still, a 404 Not Found error blocked the site regardless. Next: using the cell phone that received the message as a personal Wi-Fi hotspot. The only difference now was the request’s originating IP address. If the software was configured to present content only to requests originating from cellular networks, the page would function. This time, it did.

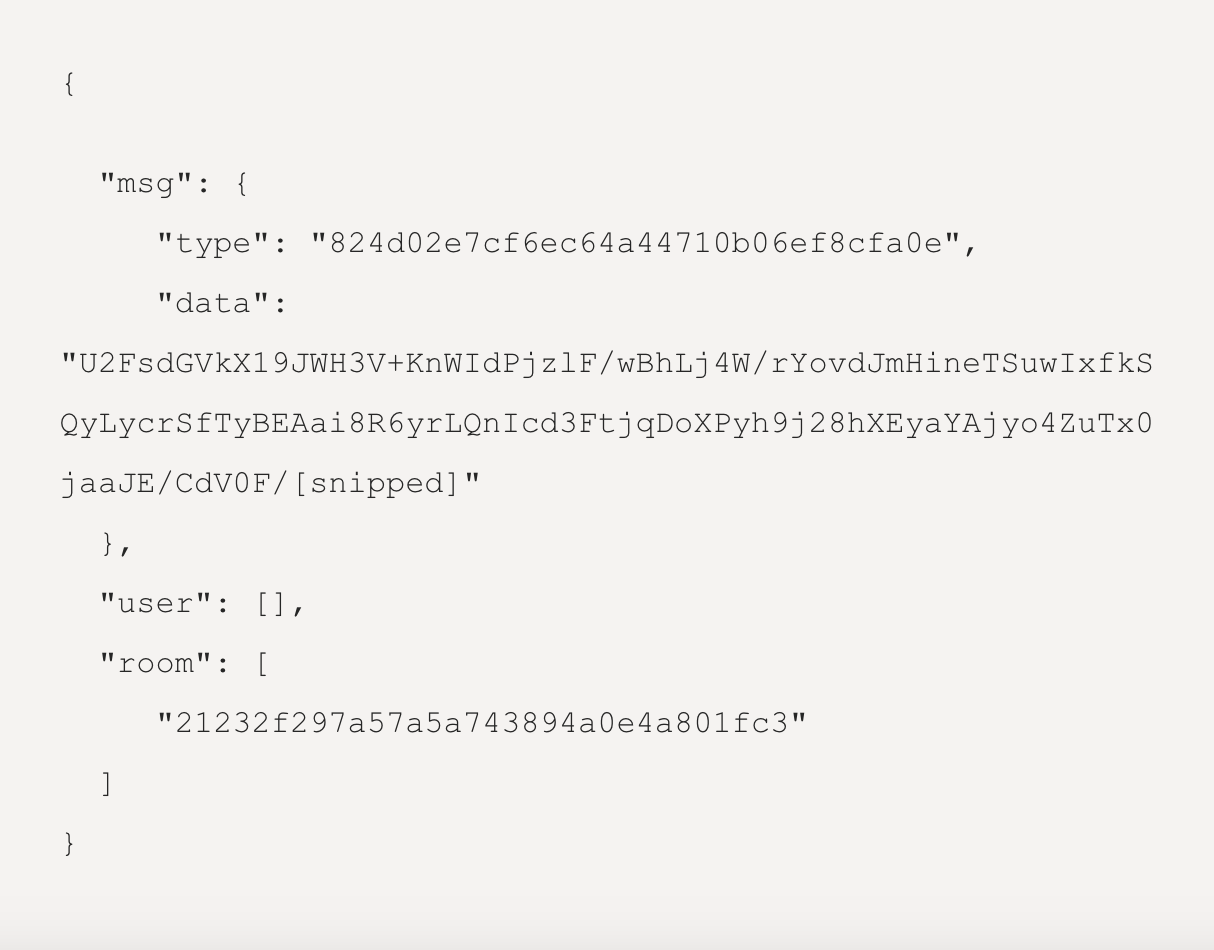

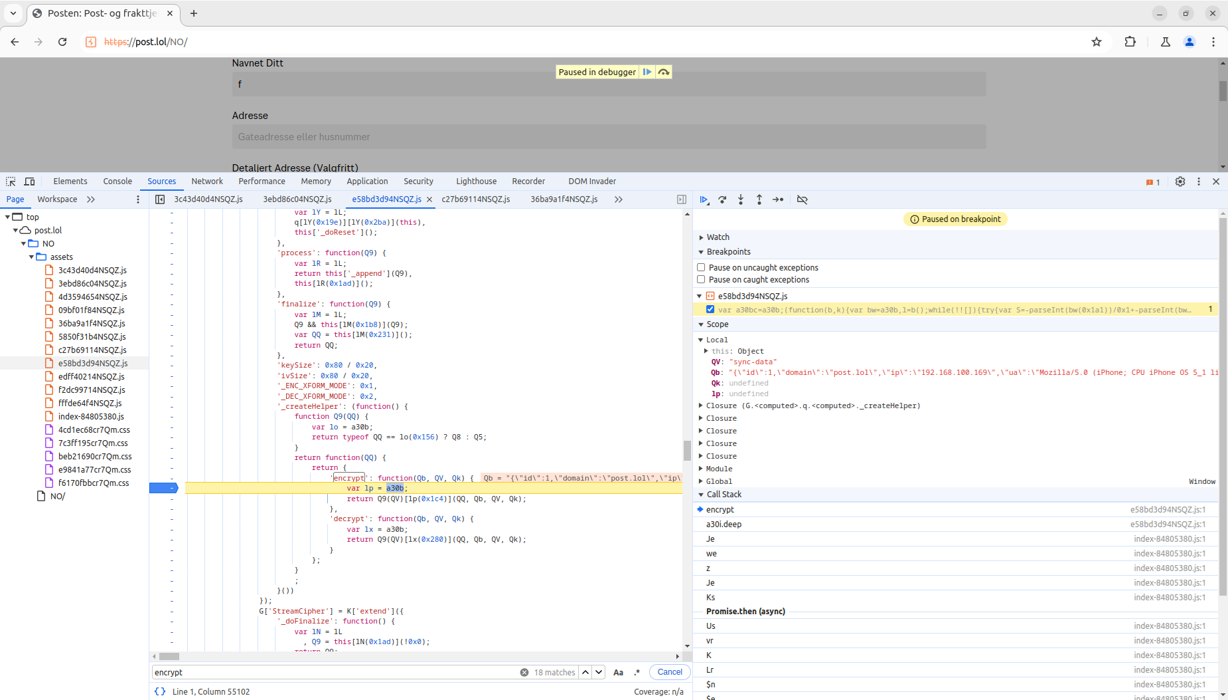

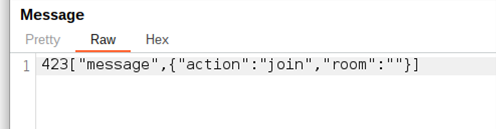

Time to crack the software that sent Erlend’s message. Once the (spare) laptop was up and running, forensics could begin in earnest. Immediately, the researchers recognized the smishers were communicating with each other, using a common messaging library. From the character sets and message elements, “type” and “room” seemed to be an MD5 hash. “Data” seemed to be a Base64 encoded string. Decoding the data element yielded indecipherable text, and a string: “Salted_”.

Even more encryption was at play. For most sites, the internet already has sufficient security built-in (like HTTPS). Why go further? Harrison and Erlend describe this kind of client-side encryption as “suspiciously excessive”, and “more often than not… an indication that somebody has done something fishy (pun intended).” The purpose of this encryption was to obfuscate the application’s inner workings from exactly who was digging in – security researchers who investigate scams.

What its creators didn't count on was said researchers’ masterstroke. By taking control of the client, Harrison and Erlend could inspect the messages before encryption happened, making off with the encryption keys to boot.

In the client-side Javascript code, it was clear which library was in use, which algorithm powered the encryption, encrypt and decrypt functions and keys. This inspired an idea. Harrison and Erlend wrote their own Javascript to unscramble the messages. With “a few quick lines” of code, they could see exactly what was going on. They could read, understand and even edit behind the scenes.

The Chatroom

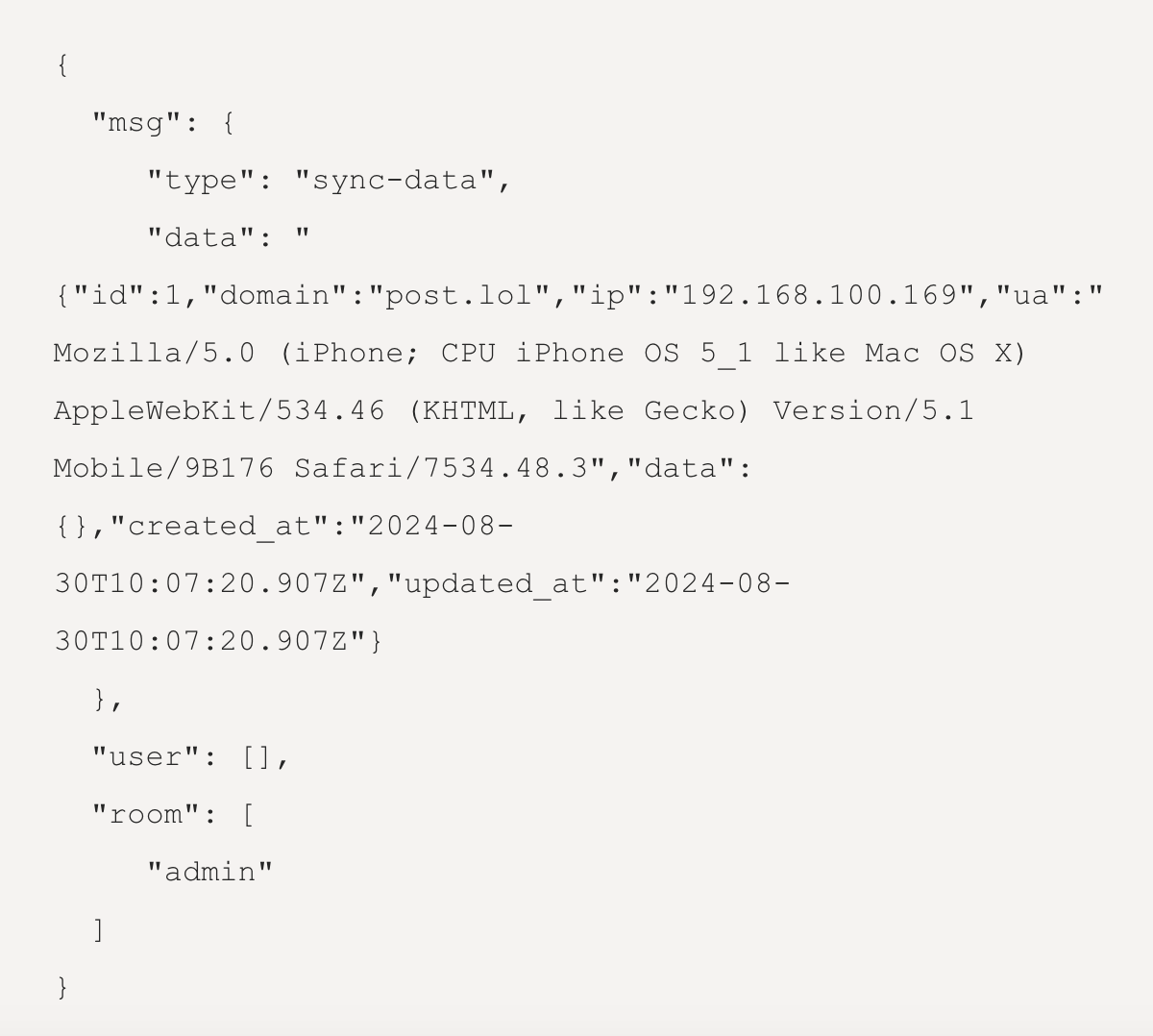

The messaging function was part of something more sinister. The researchers had opened the door to a chatroom. Could this be a version of a smishers’ Telegram group, built-in? The reality was worse. This chatroom functionality was communicating victim data.

When a potential victim loaded into the page, they would join an empty default “room”; a message on Harrison and Erlend’s spare laptop confirmed it. When the laptop typed in data, these messages arrived in a “room” called “admin”. Harrison and Erlend’s assumption was that individual application components could join “rooms”. However, to make this work, a smisher would need a central “dashboard” to see everything collated. Maybe, the two researchers thought, that dashboard was in “admin”. Like the urge to click the link in the first place, Harrison and Erlend had a hacker’s brainwave. “What if”, instead of posing as a victim, “we joined the admin room?”

“What we saw shocked us. Flying by our screen was a stream of names, addresses, and credit cards, a real-time feed of hundreds of victims being phished. Everything they typed in, character by character, we could see on our screen…” – Erlend L. and Harrison S., Cybersecurity Researchers [Source: Mnemonic]

This side project had just got serious. Harrison and Erlend had an appointment with ‘Darcula’.

Anatomy of a Scam: Inside a Criminal Phishing Platform

“Our research started to reveal just how big and professional the operation was.” – Erlend L. and Harrison S., Cybersecurity Researchers [Source: Mnemonic]

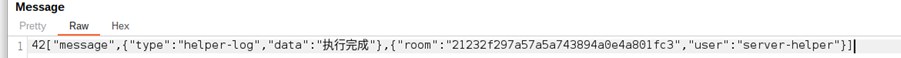

It took time for the shock to subside. Once the dust had settled, Harrison and Erlend made a realization. Alongside the victim data were some technical logs, one of which revealed the database’s name. It “kind of sounded like a username”.

Searching Google gave very few results, mostly overwhelmed by information about the dark-mode text editor palette of the same name. Around this time, the arrest of Telegram boss Pavel Durov was making the news, cementing the platform’s growing reputation as a safe haven for criminal networks. Harrison and Erlend took a look, and found a Chinese-language group: the notorious ‘Darcula’. They also found a user of the same name in place as the group’s administrator.

Harrison and Erlend saw the aforementioned tools of the smishing trade: phones loaded with credit cards in Apple Pay, hordes of SIMs and payment terminals. They saw the callousness and conspicuous consumption of a smishers’ paradise… but also lots of cats.

At the top of the group was a pinned message. On it was a detailed installation how-to for the phishing software itself. Stunned again, the researchers quickly installed a copy on the spare laptop according to instructions. The name of the software that had been used against Erlend (and countless other victims) made the group’s feline obsession make sense. It was called Magic Cat.

Licensed to Smish

“In the hands of a person and a network with malicious intentions, Magic Cat is an incredibly effective weapon.” – Tom Espen Weie, Head of the Department for Economic Crime at Sparebank1 SMN [Source: TV2]

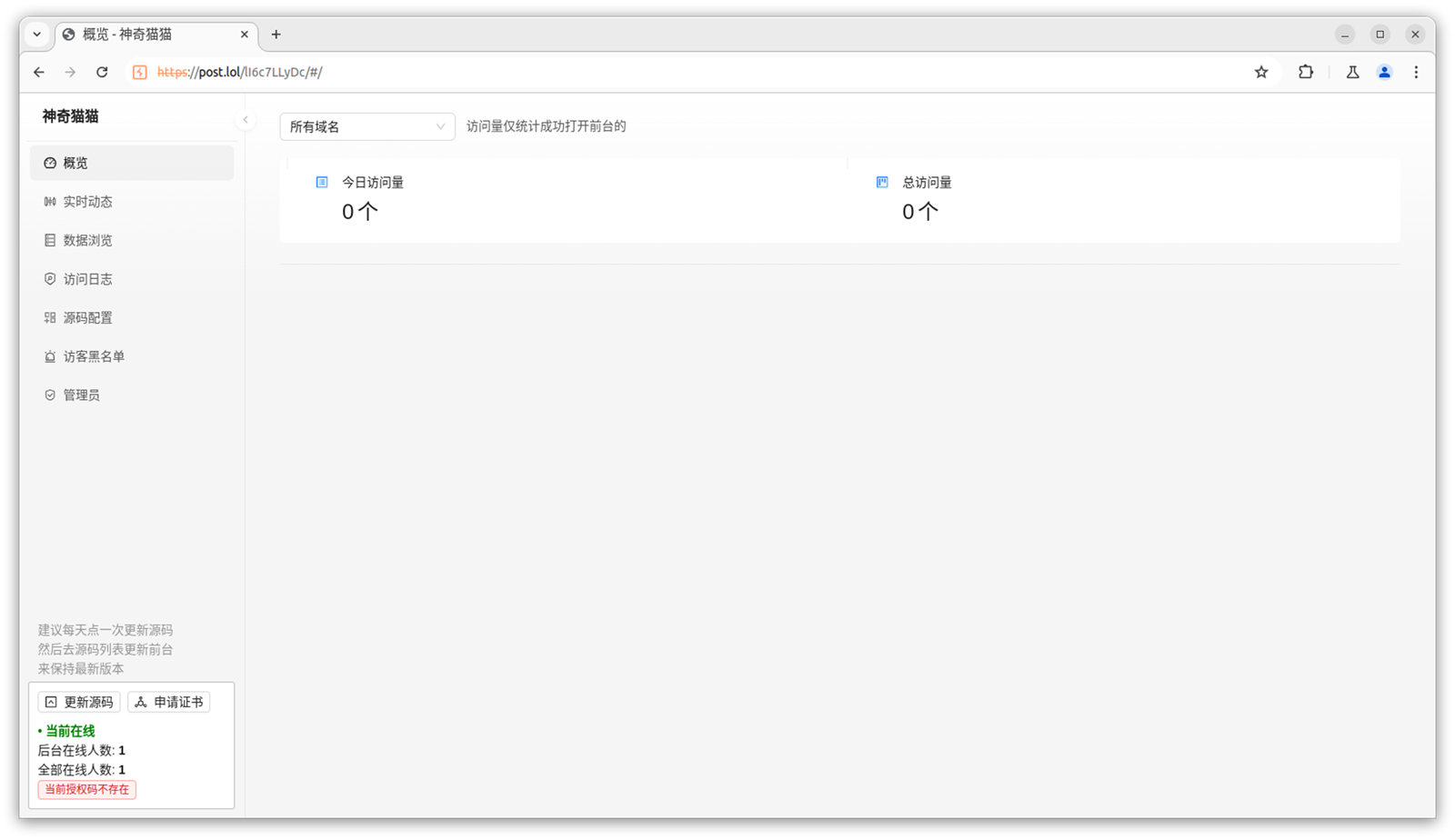

The installation had been as simple as copy-pasting one command. Now, Harrison and Erlend had access to a hidden operator dashboard, collating all a potential smisher’s stolen credit card data, and even allowing them to interact with victims. The catch? The spare laptop’s installation was unlicensed. The irony of licensing a piece of criminal software aside, Harrison and Erlend had to find a way to remove the little red red message in the corner of their dashboard. No license key, no phishing campaign.

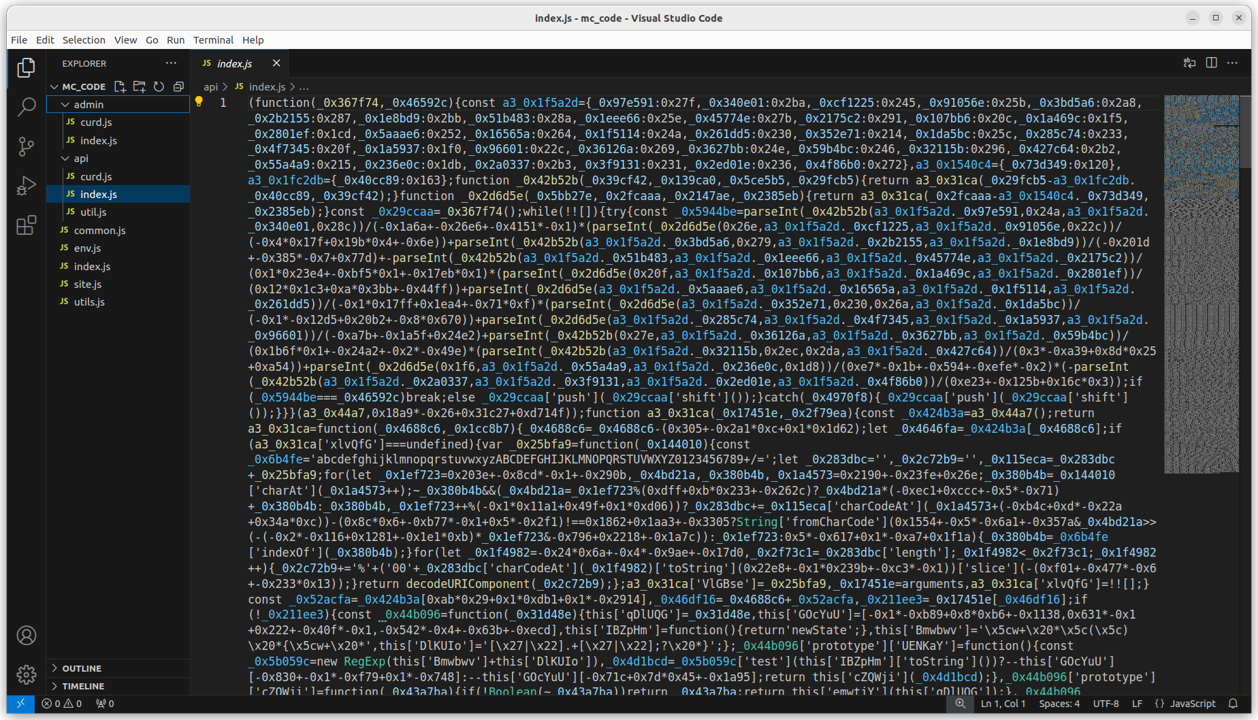

Poking around in the backend code "wasn't exactly straight forward”. Magic Cat’s developer was enthusiastic about encryption, and this enthusiasm extended to obfuscating the platform’s inner workings too. Attempting to peek behind the final curtain resulted in “unintelligible muck”.

Luckily, these researchers are open-source enthusiasts. Open-source software exists that could de-obfuscate the output from the developer’s Javascript Obfuscator. The result: albeit minus the original identifiers and comments, readable code.

Readable backend code meant Harrison and Erlend could see how Magic Cat worked. Not only could they understand functions related to the generation of their much-needed activation key, but also the extent of Magic Cat’s activation infrastructure. Wrapped up in every copy of the software was a fully-fledged activation system. Via a hidden menu, a user could trigger the functionality to generate activation keys and activate other copies of Magic Cat. All copies of Magic Cat could generate keys, as well as consume them.

This meant the spare laptop could activate its own software.

“The software required us to first generate a new license, add a comment to it, specify the license's expiration date and the limit of phishing templates each license is eligible to download…” – Erlend L. and Harrison S., Cybersecurity Researchers [Source: Mnemonic]

These features had the professional sheen of enterprise software licensing, as if Magic Cat’s developers were concerned with keeping tidy books. The software also logged the IP address of any and all phishing servers it received activation requests from. From their controlled lab environment, Harrison and Erlend were able to trick the program; it thought the spare laptop was a real activation server, and activated its own copy of Magic Cat without the need to buy a license.

The researchers had gone undercover. They had convinced Magic Cat they were smishers themselves

Inside Magic Cat

“It’s feature rich, and clearly developed to enable non-technical buyers to conduct their own phishing campaigns at scale.”– Erlend L. and Harrison S., Cybersecurity Researchers [Source: Mnemonic]

What was it like to smish with Magic Cat? Disturbingly easy. Harrison and Erlend wagered even the least tech-savvy users would be competent cybercriminals. This platform was presented like a piece of commercially available software; a criminal tool operated like Photoshop, or even a live service game.

Magic Cat had regular software updates, software release cycles, feature announcements advertising new ways to scam vulnerable people. The bookkeeping, as expected, was complete. Like the installation guide, Magic Cat even offered troubleshooting and support for smishers with a malfunctioning copy.

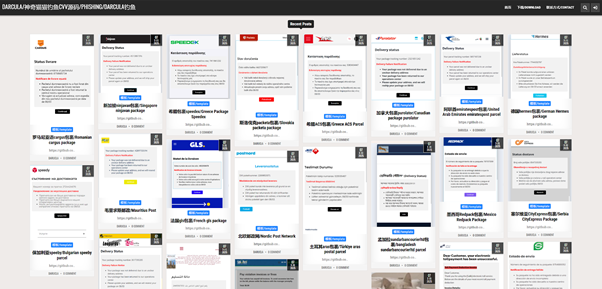

Worst of all was Magic Cat’s brand library: out-of-the-box support to impersonate a choice of hundreds of global institutions and corporations. At the time of their investigation, NRK discovered a range of over 300 fake websites to choose from; this is a common feature for phishing programs, the nearest competitor offers only thirty. Recent updates to Magic Cat reportedly offer smishers tools to build their own custom brand templates too - an effort to improve the software’s user-friendliness.

It was easy, and it was working. Magic Cat streamed data entered by victims in real-time to the operators, and watching victims give away life-altering data character-by-character was gut wrenching. A smisher could steal details, then request authenticatiPIN codes in real time, breaking down the final barrier to financial devastation.

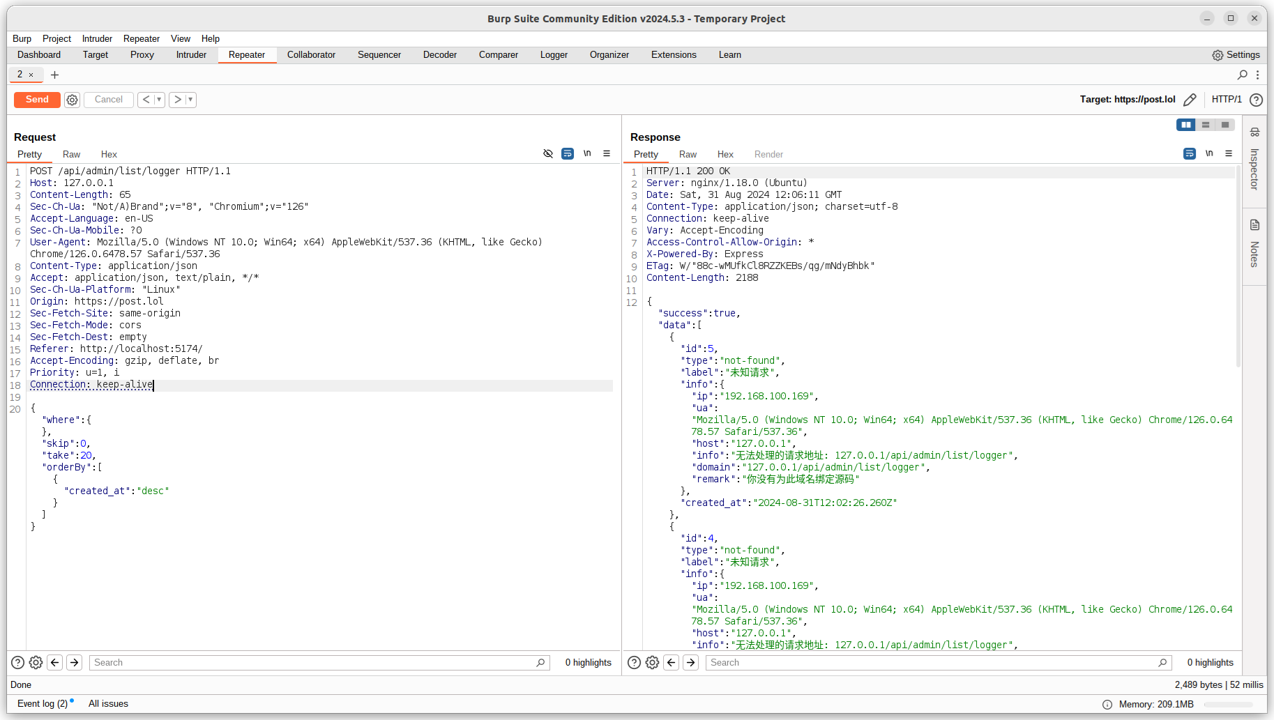

It wasn’t enough to sit watching in horror. While logic checking aspects of Magic Cat, Harrison and Erlend noticed another gap in the software’s armor. If a set of parameters from the HTTP request matched, a user could skip authentication and authorisation altogether. A user could perform queries without having to log in. That is, without being tracked.

“It’s possible this was an oversight by the developer… Or, if you want to put your black hat on and think a bit more dubiously, it would be a very good backdoor with plausible deniability built-in - in case anybody was to discover it in the future.”– Erlend L. and Harrison S., Cybersecurity Researchers [Source: Mnemonic]

All sorts of things were unexpectedly built-in to Magic Cat. Could plausible deniability be one of them? Could this be a backdoor?

And even if it wasn’t, did ‘Darcula’ develop it? Who was ‘Darcula’ anyway?

Curiosity Caught the Cat: Unmasking Darcula with OSINT Industries

“At this point we were not even certain if Darcula was a person or a group.” – Erlend L. and Harrison S., Cybersecurity Researchers [Source: Mnemonic]

By January 2024, Harrison and Erlend had compiled their report for several law enforcement agencies. However, the biggest question remained unanswered. The researcher’s infiltration work had been stellar, but finding ‘Darcula’ would require a different set of skills.

For the human element of their investigation, it was time to turn to OSINT - and OSINT Industries.

Amidst the figures and Ferraris in smishers’ Telegram groups, their quarry had his only online presence: mundane technical updates about his creation, Magic Cat. As leads for his identity, these were negligible. Better to turn back to the software’s data ecosystem, and start sifting through. At last a lead: an IP address related to admin functions.

An IP address

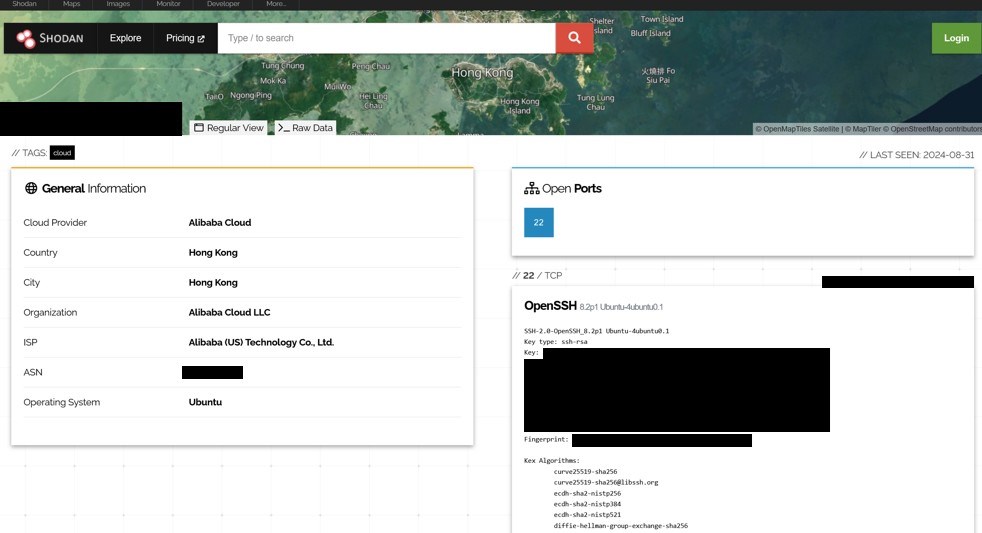

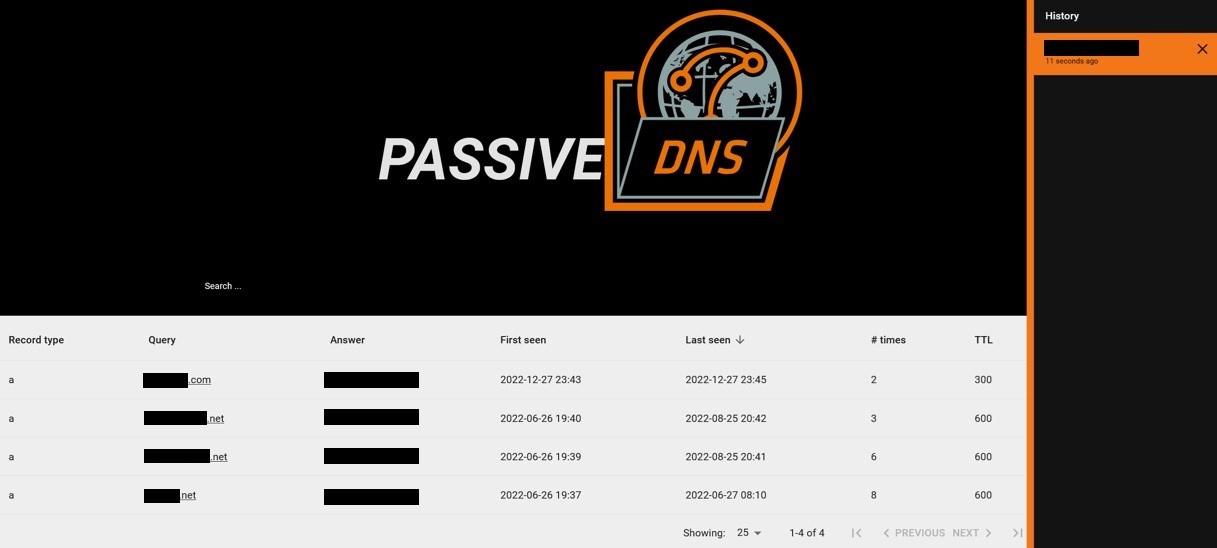

An IP for a virtual machine or VPN in Alibaba Cloud was a weak lead, but better than nothing. It could be Darcula’s custom creation, or equally a shared source with thousands of co-users. Harrison and Erlend’s research with passive DNS records indicated this IP had a past, a little over a year before their investigation began: it linked to a domain that in turn raised a GitHub username.

The reuse of the IP confirmed the IP was “a weak link”. Still, there was hope. The GitHub repositories contained software built with the same framework as Magic Cat.

Startlingly, the commit history of these GitHub repositories revealed the user’s Gmail account. For these two OSINT Industries users, the weakest link just became the strongest.

An email OSINT search was required.

Enter OSINT Industries

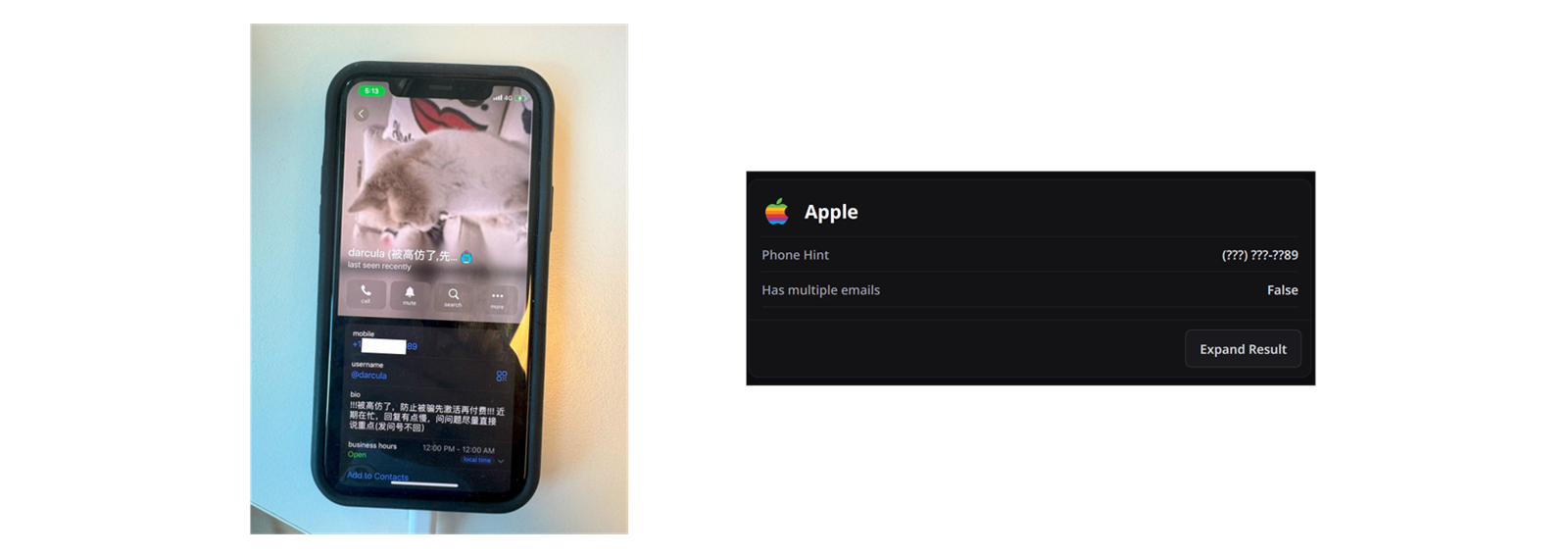

Running the Gmail account through OSINT Industries brought up instant results. Darcula’s Telegram profile was attached to a US phone number ending in 89, which Harrison and Erlend had previously disregarded as a likely burner. However, OSINT Industries had revealed a link between this Gmail account and an Apple ID – also with a phone number ending in 89.

If the GitHub user was still using the same VPN server, this was most likely the feline fanatic phishing boss himself. Thanks to OSINT industries, Harrison and Erlend had avoided accidentally disregarding the most conclusive intel so far. It was now that the researchers decided to play Darcula at his own game. They had access to Magic Cat, a piece of software their target had developed expressly for one purpose: to steal user data. Could the smisher be smished, for good?

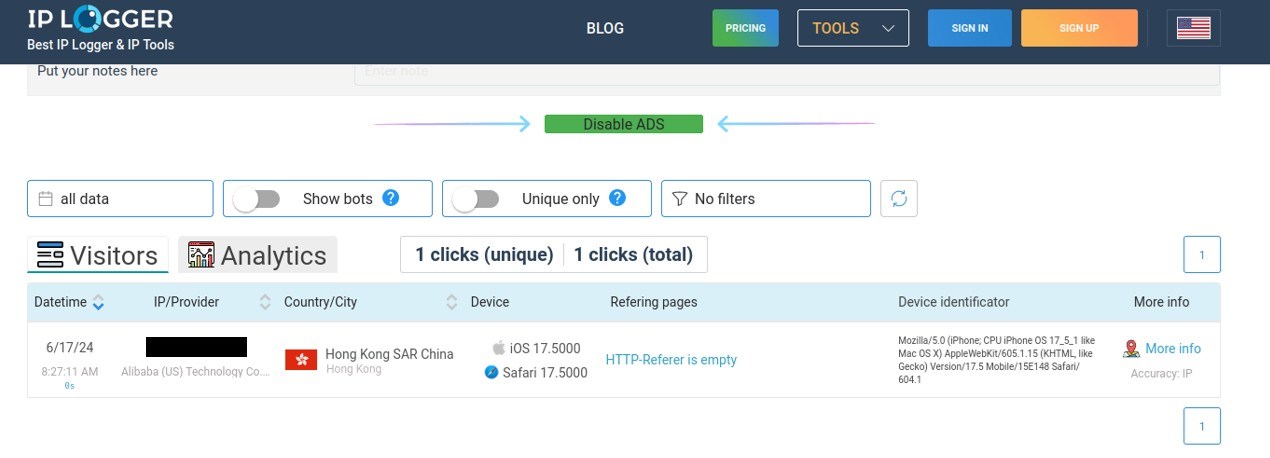

What if they sent an email to the Gmail address, containing a link? If Darcula clicked the link, his IP address would be recorded. Just like Erlend all those weeks ago, Darcula’s curiosity got the better of him. But this time, curiosity killed the cat.

Not only was the email address confirmed as active when whoever had access clicked the link, but that person’s IP address matched the one listed in Magic Cat. If this was Darcula, the click was coming from Hong Kong.

Something else had come from the OSINT Industries search. Harrison and Erlend had uncovered a partial Chinese phone number also linked to Darcula’s suspected Gmail account. When applying for a phone number in China, proof of identity is required; making Carcula’s full Chinese phone number an invaluable identifier. Another email address had come up while sifting website data. Running this through OSINT Industries exposed an account on Chinese messaging and email platform QQ. A cat video on the account’s linked YouTube showed a smartphone screen with a Chinese phone operator in the corner. Soon, Harrison and Erlend’s OSINT uncovered a Chinese phone number – missing only three digits.

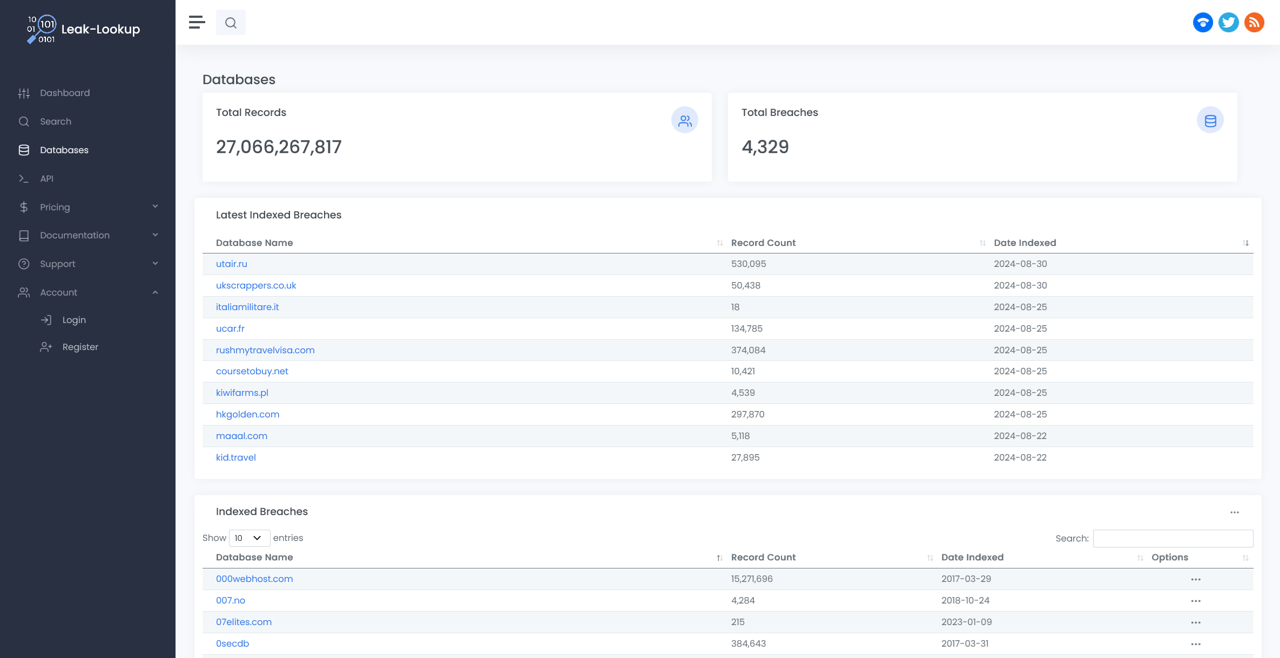

Three missing digits meant 1000 possible numbers. The researchers had to narrow this number down. Only those with online presences could realistically be Darcula’s: scanning breach databases manually would give them only the best candidates for an OSINT Industries search.

This strategy led Harrison and Erlend to a phone number with an Instagram account attached. An Instagram account with the same username as the suspected Darcula Gmail account, and the same profile picture.

“It was a shot in the dark…” – Erlend L. and Harrison S., Cybersecurity Researchers [Source: NRK]

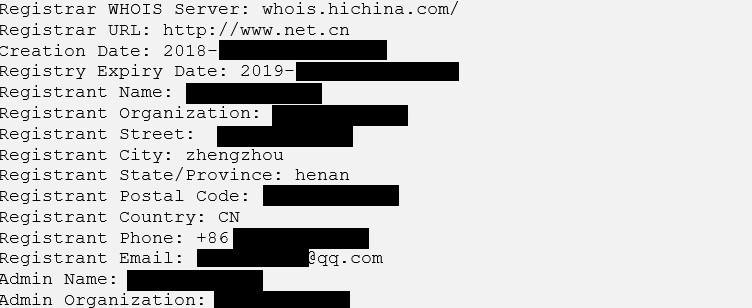

This was a likely phone match. Next, WHOIS records, in case a website had been registered with that number. This yielded more than a hit: a full name, a phone number, and a location.

With these credentials, the user had uploaded on a now-defunct blog multiple Word documents with instructions on how to install and use Magic Cat. A name was listed in the document metadata as the author.

Darcula was likely to be Yucheng C., a 24-year-old Chinese man from Henan province.

The Mnemonic researchers’ associates at NRK reached out to Yucheng C., a.k.a. Darcula. Someone using the alias ‘Lao Liu’ responded on his behalf:

"Yucheng, I wish to speak with you."

“Yucheng is employed by our company. He resigned a week ago.”

"Why did Yucheng resign?"

“It might be due to you, so I need to know what you want.”

NRK were sceptical that Darcula had really abandoned his creation. They responded that they wished to talk about Magic Cat, and the identity of its creator. ‘Lao Liu’ confirmed that Yucheng C. was “one of the founders of Magic Cat”, but in typical obfuscating style, insisted that he was only part of a salaried group: “just one of the technologists who developed the program”.

NRK pushed harder. They had documentary proof that Darcula was assisting people using Magic Cat for phishing, via Telegram.

“How do you explain this?"

“We only sell the software. We do not know the users.”

"Are you aware that Magic Cat is used for fraud?"

“I know, we will shut it down.” – Interview with ‘Lao Liu’, NRK. [Source: TV2]

This was a lie. Just as Harrison and Erlend had submitted their report to police and NRK published its investigation, a new update was dropped for Magic Cat. While the investigation was expanding to include Le Monde and Bayerischer Rundfunk, Darcula and his team had been hard at work. In NRK’s words, this new version of Magic Cat “makes it even easier to deceive people and take their money.”

The Victims

As this story comes to its conclusion, little has been said about the victims of Darcula and Magic Cat. After all the technical details and slam-dunk evidence, the flickering characters that stream into this criminal software’s dashboards come from thousands of very real people. Behind each statistic is someone like 73-year-old Bjørnar Skogstad.

NRK found him living a quiet life, in a yellow house beneath the towering Svartfjell mountain on the Norwegian island of Senja. In the most unlikely paradise, Bjørnar had fallen victim to an international cybercrime network.

One January day, a seemingly urgent text about an unpaid Autopass bill for toll road crossings arrived. Trusting and meticulous, Skogstad had made an innocent mistake: he clicked the link. He entered his card details without hesitation. By the time he realises there are no toll roads on Senja, 1,900 kroner was irretrievable.

“I was shocked by how many victims there were...” – Harrison S., Cybersecurity Researcher [Source: Mnemonic]

Analysis by BR found more than 900,000 Bjørnars worldwide from late 2023 to summer 2024, all of whom had unwittingly provided credit card information to thieves. BR found 20,000 German victims, speaking to 100 in person; Le Monde found at least 9,000 in France.

Many are too ashamed to admit what happened. When Bjørnar reported the scam to police, they considered it too minor to pursue. At least Harrison and Erlend’s work with OSINT Industries makes it possible to determine who caused his pain. Skogstad’s voice tightened when NRK showed him pictures of the scammers’ ostentatious Telegram group. “If they had dared to meet me face to face”, he said, “I would have beaten them to death”.

All the while, Farsi, Bjørnar’s loyal cat, was curled up in the garage. It’s to his cat that Bjørnar turns for comfort.

To find out more about Harrison and Erlend’s work, visit:

https://www.nrk.no/dokumentar/xl/inside-the-scam-network-1.17399135 [English]

https://www.nrk.no/dokumentar/xl/the-hunt-for-darcula-1.17399157 [English]

https://www.br.de/nachrichten/deutschland-welt/falsche-dhl-nachrichten-wer-dahinter-steckt,Uk2pzV7 [German/Deutsch]

https://www.lemonde.fr/pixels/article/2025/05/04/votre-colis-n-a-pas-pu-etre-livre-enquete-sur-les-arnaques-a-la-carte-bancaire-par-sms_6602832_4408996.html [French/Français]

Start your free enterprise trial

Get Free TrialReveal what's behind any contact, instantly.

We want to hear your story!

Inspire Others

Educate about what OSINT can do.

Positive Publicity

Share your success with the world.

Support #OSINT4Good

Be part of the OSINT story.