Try the world's most popular OSINT platform for free. Elevate your enterprise investigations with unmatched accuracy.

Brazil. The world’s biggest producer of coffee, orange juice, FIFA World Cup wins – and, as the OSINT reveals, mobile Trojans.

“[There is] a need to digitally re-educate Brazilians, and get them to adopt safe habits in their digital routines…” – Angelica Mari, Senior Contributor on Behavior and Technology for Forbes. [Source: Forbes]

It looks like a real app, but the Brazilian mobile Trojan has one simple aim. Download this malware onto your smartphone, and say goodbye to your data, your messages, and (most crucially) your banking app security. With 212 million residents in the world’s fifth-largest country, there’s enough victims to go around. Brazil has helped pioneer a distinctly Latin American flavour of banking Trojan malware: Guildma, Mekotio, Casbaneiro, the “Tetrade” group (Javali, Melcoz, Grandoreiro). Recent discoveries like CHAVECLOAK suggest this ecosystem and developer culture shows no sign of diminishing, or losing its regional quirks.

Brazil’s dominance in this particular type of malware springs from conditions that foster particularly high-yielding soil for at-home scams. One ingredient in this fertilizer is Pix. The Brazil-only payment system launched by the Banco Central do Brazil (BCB) in 2020 is how 80% of Brazil’s population move money – not cash. To share a ubiquitous instant transfer app is productive for Brazilian commerce; also for any criminal looking for a dupable app with an instant cash-out. The BCB claims that Pix is fully traceable, but judging by recent IMF warnings about Pix as an instant payment rail, this doesn’t bear out. To add to the mix, Brazilians exist in the mobile-first reality that dominates the Global South; Android’s mobile OS share in Brazil stands at roughly 87%.

With conditions like these, it’s easy for attackers to see incentives from the development end. It’s easy to concentrate R&D on one single strand of guaranteed-return malware, and to build a community for cybercriminals all working on the same scam. Brazilian cybercriminals thrive (like most worldwide) on Telegram; the usual sharing of phishing kits, stealer logs, droppers, and command channels takes place here, alongside social engineering (“golpe”) operations tailored for the Land of the Palms. IBM’s analysis of mobile Trojan software PixPirate showed these criminals have developed highly-targeted and persistent tactics aligned to local banking workflows and cash-out habits in a way that indicates one thing. Ubiquitous Androids + an app like Pix = high ROI for mobile-first malware. For Brazil’s scammers, the recipe is obvious.

Local law enforcement often struggle to cross a country as large and rural as Brazil; the most successful operations have involved Interpol, resulting in the arrests of handfuls of programmers. However, OSINT offers a faster solution.

In a groundbreaking use of OSINT Industries, an anonymous OSINT investigator has demonstrated how one data point can crack open one of Brazil’s most nefarious Trojan operations, and identify its developer. With OSINT Industries, he reveals an extensive cybercrime operation involving malware development, online fraud, and multiple data breaches – and exemplifies the power of automated OSINT tools.

The Target: Leonardo Patrick, alias “go1ano”

Abadia dos Dourados, Minas Gerais, sits in the valley of the Dourados River. The small rural Brazilian municipality gets its name from the combination of this river and its little 1886 chapel, built in dedication to Nossa Senhora da Abadia (‘Our Lady of Abadia’). Founded by 19th-century prospectors drawn to diamonds hidden in the riverbanks, farmers soon joined to cultivate the corn, cattle, rice, soybeans and famous Brazilian coffee plants that fill local fields. The architecture is traditional, the landscape lush and the population tiny, with just 7000 abadienses in residence.

It’s the last location you’d expect to find a cybercriminal mastermind.

A user known as “go1ano” is suspected of creating and spreading malicious Trojan software; more specifically, the GhostSpy Android Remote Access Trojan, or RAT. This software can hijack an Android smartphone to take full control with shocking ease. The compromised device can execute remote command execution, keylog, and even record audio or video – facilitating the theft of banking credentials, 2FA codes, SMS messages, call logs and contacts.

Lucky for our anonymous OSINT investigator, go1ano isn’t quite a genius. This investigation began with exposure of a single crucial identifier: an email address, “leeonardopatrick@gmail.com”. This email address was potentially obtainable from a number of sources, either one of Patrick’s online profiles or one of the numerous data breaches to which he had (ironically) fallen victim. What mattered is that this single data point was in an OSINT investigator’s possession – and that investigator had access to OSINT Industries.

Soon, this anonymous OSINT investigator uncovered Patrick’s domains, breached accounts, and development link to the GhostSpy mobile Trojan. Both his legitimate and cybercriminal personae would be exposed. Soon, go1ano would be unmasked once and for all.

The Gateway: One Gmail Address, Unlimited Leads

With access to the leeonardopatrick Gmail address, the first step was an email search on OSINT Industries.

Thanks to our tool’s automation, it was possible to simultaneously search the address suspected to match go1ano’s true identity across LinkedIn, Medium, Apple, Twitter, Pinterest, Adobe, IQ Option, Wix, InfoJobs Brazil, 4Shared, and all Google services. Active accounts were identified on all of the above, revealing:

Google/Gmail – A primary account with unique ID (“ID:10869*****4994”)

LinkedIn – A professional profile (privated)

Medium – A publishing platform account (“leeonardopatrick")

Google Play Games – A gaming profile ("LeonardoPatrick")

Apple – Account with partially masked phone number

Twitter – A confirmed presence and active account

Pinterest – A registered account

Adobe – A registration with Adobe services

IQ Option – Options-trading activity

Wix – A signup for website creation services

InfoJobs BR – Activity on a Brazilian job portal

Shared – Activity on a file-sharing service

With this much data, it was possible to start an in-depth investigation of Patrick’s SOCMINT. These accounts were all demonstrably in use by Leonardo Patrick; he was making consistent use of his government name in legitimate contexts, and temporal analysis revealed consistent activity patterns on Google services, complete with relevant Maps reviews. He had an interest in gaming and technology. Could a link be drawn to go1ano as Patrick’s cybercriminal alias?

OSINT Industries’ WHOXY module identified two important domains. Both “mudumau.net” and “goianosorteio.com” were registered to leeonardopatrick@gmail.com.

The first, mudumau.net, was registered in 2015. Our anonymous OSINT investigator immediately speculated this could be an early attempt to typosquat on popular Medium humor blog MuddyUm. It was currently inactive, but coincided with the beginning of Leonardo Patrick's digital activities

The second, goianosorteio.com, was more suggestive. Judging by the name (“sorteio” trans. lottery, raffle or prize draw), it seemed to be a lottery or raffle scam targeting Brazilian users. The name targeted a “Goiás” audience, combining the demonym for residents of the Goiás/Central-West region of Brazil with “ano” – “year” in Portuguese. This was Leonardo Patrick’s first foray into online fraud, and he had named it “goiano”.

That these domains were not currently active was no big deal. Their existence alone showed our OSINT investigator the skills of a malware developer: long-term strategic planning with registration years before each domain’s use, activity diversification, and a lapse into inactivity that could be either an anti-detection strategy, or “backup infrastructure for future operations”.

Next, data breaches via OSINT Industries’ Have I Been Pwned module. For such an active cybercriminal, Leonardo Patrick’s security was inadequate.

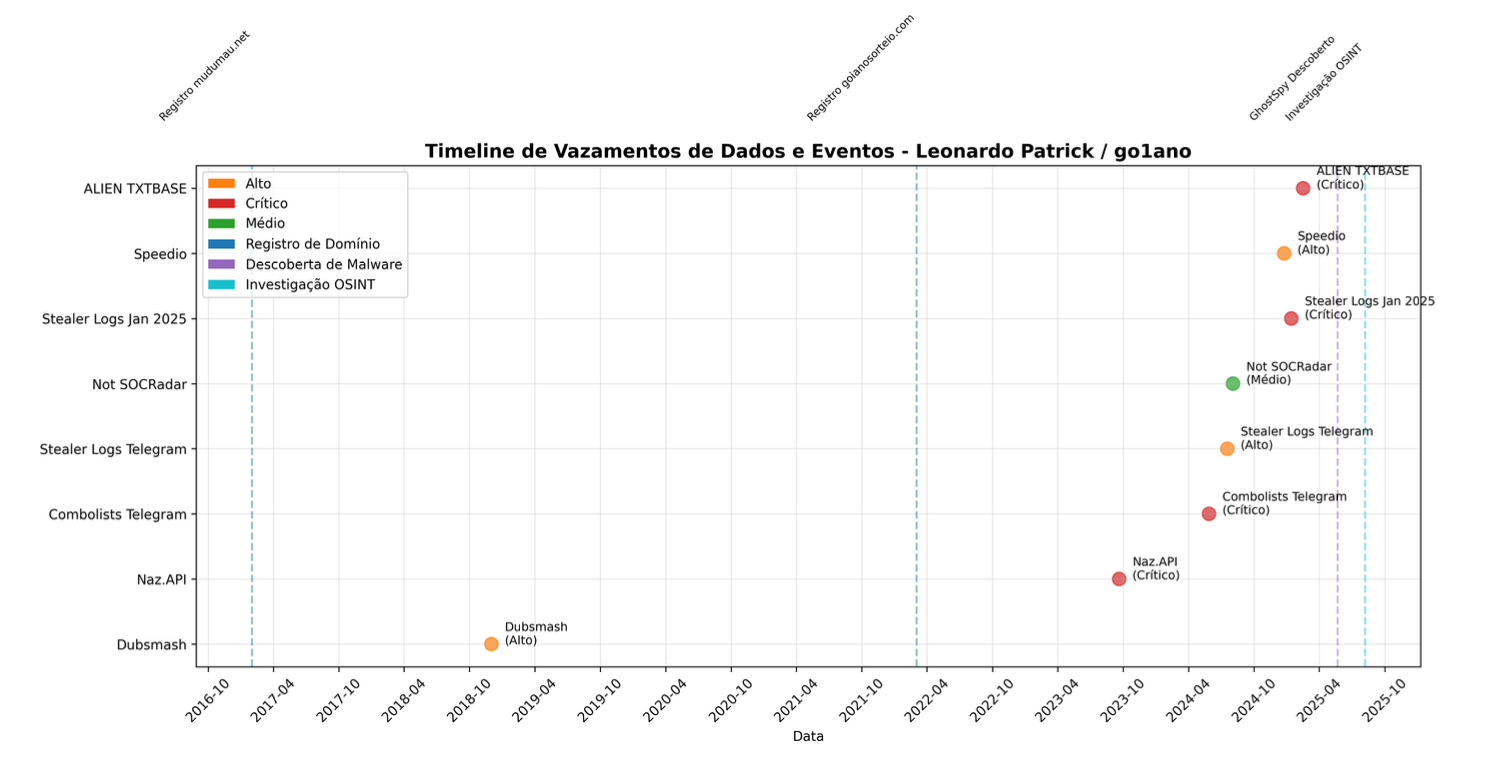

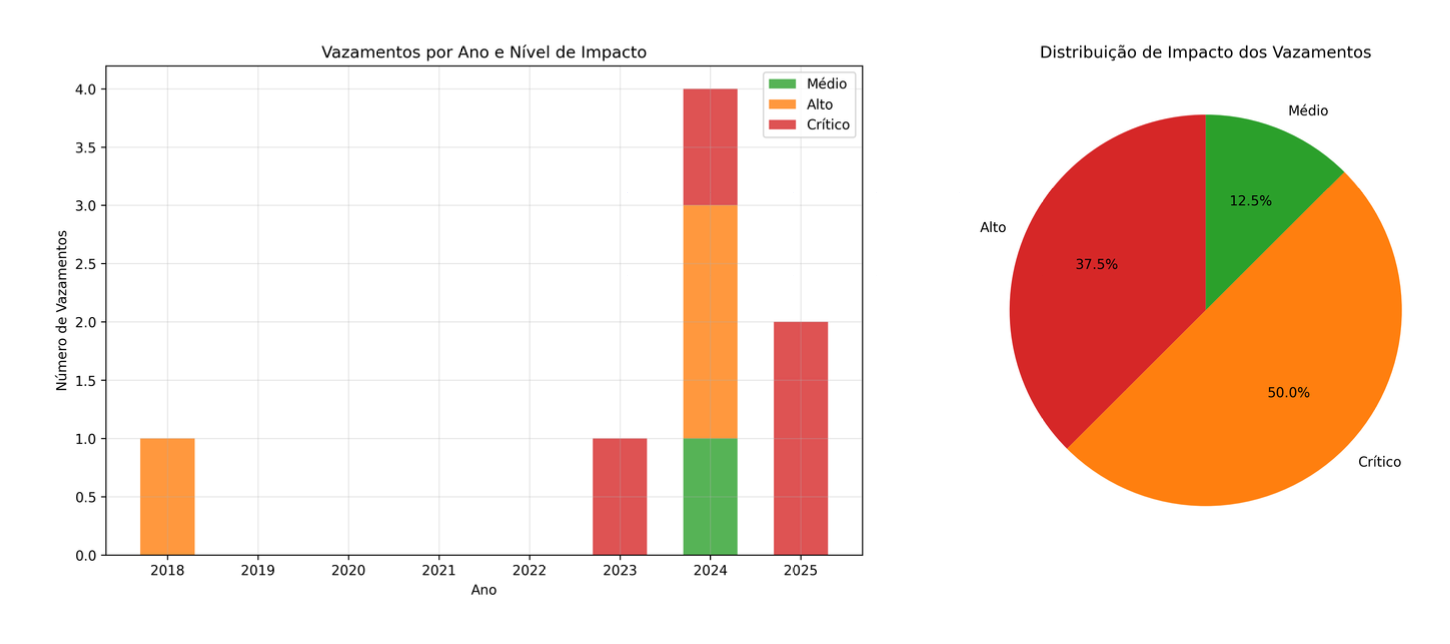

The leeonardopatrick@gmail.com address appeared in eight major breaches from 2015 to 2023, from Dubsmash to Naz.API to Speedio, alongside several other massive “stealer log” leaks from Telegram groups. Either Patrick was reusing his passwords, or had been infected by malware himself – because his passwords had been stolen again and again. Our anonymous OSINTer built a chronological list of breaches, including but not limited to:

Dubsmash (December 2018)

Impact Classification: High

Exposed Data: 162 million unique email addresses, usernames, PBKDF hashes

The first identified breach occurred in the video messaging service Dubsmash. This incident marked the beginning of Leonardo Patrick's digital exposure, with his data subsequently appearing for sale on the dark web in 2019. The presence in this initial breach suggests early use of social media platforms and possible credential reuse that would become a pattern.

Naz.API (September 2023)

Impact Classification: Critical

Exposed Data: 71 million unique emails, 100 million unique passwords

After a five-year hiatus, Leonardo Patrick reappears in the Naz.API breach… Particularly significant as it temporally coincides with the period when "go1ano" began developing more sophisticated malware. The presence in this breach suggests possible compromise by stealer malware or participation in credential stuffing activities.

Combolists Posted to Telegram (May 2024)

Impact Classification: Critical

Exposed Data: 361 million unique emails in 122GB of data

This breach represents a significant escalation, with data collected from malicious Telegram channels… This breach coincides with the period of greatest "go1ano" activity in malware development, suggesting possible connection with cybercrime communities on Telegram.

Speedio (December 2024)

Impact Classification: High

Exposed Data: 27 million unique emails, Brazilian commercial data

The breach of Brazilian platform Speedio is particularly relevant given that Leonardo Patrick resides in Brazil… An unsecured Elasticsearch instance exposed Brazilian commercial data, suggesting possible use of lead generation services or legitimate commercial activities parallel to cybercrime activities.

ALIEN TXTBASE Stealer Logs (February 2025)

Impact Classification: Critical

Exposed Data: 284 million unique emails in 23 billion lines

The most recent and massive breach, obtained from a Telegram channel known as ALIEN TXTBASE, represents the largest compromise… Leonardo Patrick's presence in this breach coincides with the period of GhostSpy malware discovery, suggesting possible connection between his activities as developer and malware victim.

These breaches weren’t evenly spaced. 70% of them had occurred in the final two years of the timeline, and a high number were stealer malware logs. This meant Patrick was getting breached not just from hacked websites, but from malware installed on compromised devices that he owned. Most ironically, several breaches came from Telegram channels where cybercriminals communicate. This, our investigator speculated, meant Patrick was both actively involved in collecting and distributing stolen details on these channels, and repeatedly infected with malware; possibly when “testing other hackers’ tools.”

However these breaches occurred, they were vital for identification. Building a timeline, go1ano and the Leonardo Patrick email were showing a strong temporal link:

2015: First domain and breach appearance.

2019: New domain tied to scams; reappears in breaches after a quiet period.

2022–2023: Peak activity, frequent breaches, and GhostSpy discovery.

This could suggest they were one and the same. After the first Dubsmash breach in 2018, Patrick had taken a 5-year hiatus. When he returned, his compromises evolved from high to critical impact and became extremely frequent; as GhostSpy grew, Patrick was breached again and again in Telegram malware groups. Simultaneously a developer and a victim, malware had become a major feature of this individual’s digital life.

The Unmasking: Go1ano’s Timeline of Escalation

In May 2025, as Leonardo Patrick was at his peak of Telegram activity, GhostSpy was discovered by cybersecurity researchers at CYFIRMA. The sophistication of this Android Remote Access Trojan (RAT) was remarkable. It was superior to anything else on the market. If this malware was downloaded in the guise of a normal app, an attacker could assume complete command of the infected device like a remote control. GhostSpy came preloaded with functions that made it tough to get rid of too. It bypassed detection by security solutions, resisted uninstallation, and maintained a presence on the device even after it was ‘deleted’; all the while, it surveilled the user desperately trying to remove it from their phone before it stole even more data and money.

Time to prove that it was Leonardo Patrick, aka go1ano, who built it.

Patterns and Correlations

The first evidence this investigation revealed with some surety was that Leonardo Patrick operates under the alias "go1ano" for cybercrime activities. The alias “go1ano” references both Goiás, the state neighboring Minas Gerais, and Patrick’s first fraud attempt at cybercrime on the raffle domain goianosorteio.com.

What’s more, GhostSpy’s discovery lined up with Leonardo’s peak breach activity, suggesting direct involvement in its development. The timeline went:

- Early activity (2015): First breach (Dubsmash) and registration of mudumau.net.

- Quiet period (2016–2018): Little or no recorded breach activity, possibly a time spent building technical skills or establishing underground contacts.

- Escalation (2019 onwards): New domain goianosorteio.com registered - its name hinting at lottery scams - and appearance in the massive Naz.API breach.

- Peak (2022–2023): Activity spiked dramatically with frequent appearances in “stealer log” breaches from Telegram, the discovery of GhostSpy malware, and multiple high-impact leaks in consecutive months.

Telegram

Telegram, beloved by cybercriminals for its firm encryption, large group capabilities, and ease of sharing massive (stolen) files. That Patrick was active in these channels indicates his role as a malware developer. Multiple branches of his details originated here. Patrick’s appearance in these data sets came during his peak phase of malware development. For him, these channels were doubling as both distribution points for his own malware, and sources for stolen credentials and other hackers’ tools.

Mapping the Two Identities

The OSINT available on Patrick showed two clear digital identities. One, “Leonardo Patrick” was a legitimate persona: the real, government name he uses for professional profiles like LinkedIn, job portals, and so on. The second, “go1ano”, was reserved for malware development: GhostSpy creator and cybercriminal ‘mastermind’.

Central Node: Leonardo Patrick

Direct Connections: 15 identified

Connection Strength: Ranging from 2 (secondary platforms) to (primary identities)

Connection Types: Personal, professional, technical, malicious

Our anonymous investigator began to visualise the connections between them, mapping between three clusters: Patrick as central node, the government-named “legitimate identity” and “goi1ano”:

1. Legitimate Identity Cluster

Leonardo Patrick (physical person)

leeonardopatrick@gmail.com (primary email)

LinkedIn profile (professional activity)

Abadia dos Dourados, MG (location)

2. Cybercrime Activity Cluster

go1ano (cybercrime alias)

GhostSpy malware (development)

Other malware (associated activities)

Suspicious domains (infrastructure)

He then analysed the strength of these connections, classifying each one on a scale of 1-5:

Strength 5 (Critical): Leonardo Patrick ↔ goano - Leonardo Patrick ↔ leeonardopatrick@gmail.com

Strength 4 (High): go1ano ↔ GhostSpy - Leonardo Patrick ↔ registered domains

Strength 3 (Medium): Email ↔ critical breaches - Leonardo Patrick ↔ location

Strength 2 (Low): Email ↔ various platforms

There was a clear separation between the target’s legitimate activities (as Leonardo Patrick), and his work on malware (as go1ano). The “bridge” between them, our investigator found, was the email address that had started it all. Both identities connected to it.

This single data point, enriched by OSINT Industries, led to the creator of GhostSpy.

OSINT Industries and Threat Detection

OSINT didn’t just support this investigation. It was the investigation. What’s more, with OSINT Industries, the threat detection potential of even one data point is huge. All of these discoveries came from enumerating one email. By simply inputting the leeonardopatrick Gmail address into OSINT Industries, our anonymous investigator was able to conduct a comprehensive automated search of Leonardo Patrick’s digital presence to find what he was looking for.

One OSINT Industries search revealed years of compromised accounts; from here, our investigator could build a timeline, and connect the dots from an innocent email to a cybercriminal career. OSINT Industries runs over 1000 modules in parallel, correlating data across platforms that would take a human researcher weeks to cross-check. This anonymous investigator found automation revolutionized his work, to the point of assisting him in generating the case report that became this Case Study.

Three lessons stand out. First, for Brazil’s ordinary, non-criminal users: password reuse and weak account hygiene are a recipe for disaster when your financial life relies on mobile-first banking. Second, for the law enforcement that received this case report: Brazil’s landscape may be too vast and rural for traditional policing on cybercrime, but OSINT can cut through. Criminals like go1ano may think themselves undiscoverable in somewhere like Abadia dos Dourados, surrounded by miles of farmers’ fields or sweltering jungle. With tools like OSINT Industries, they aren’t.

The wider security community can take from this the lesson that OSINT automation is a superpower. The Internet is the only place more vast and impenetrable than the Amazon rainforest; when you can scan it all at once, you can expose the creator of one of Brazil’s most dangerous Trojans in a fraction of the time.

Victim/Perpetrator

One fascinating aspect of this investigation was a rare glimpse at a hacker learning on the job. From 2015 to 2018, Patrick’s digital trail was clumsy, limited to basic breaches and small experiments. By the 2019 to 2021 period, his footprint expanded to new domains, bigger breaches, wider exposure – as go1ano learned to be a ‘better’ cybercriminal. By 2022–2023, he was pushing GhostSpy.

Watching go1ano’s development highlighted an irony. Patrick was both a perpetrator and a victim of malware. His details were stolen over and over, appearing in stealer logs; his passwords were reposted in the very Telegram groups he used to distribute malware. The same underground market that made go1ano a star developer also made him a target. In cybercrime, even outlaws are fair game.

Start your free enterprise trial

Get Free TrialReveal what's behind any contact, instantly.

We want to hear your story!

Inspire Others

Educate about what OSINT can do.

Positive Publicity

Share your success with the world.

Support #OSINT4Good

Be part of the OSINT story.