Try the world's most popular OSINT platform for free. Elevate your enterprise investigations with unmatched accuracy.

Smuggling and corruption have always marked the US-Mexico border. OSINT helps journalists like Luke Harold expose them.

“When we open up these containers, and it’s well over 105 degrees with no ventilation, no personal protective equipment, such as masks, no water… I saw these little kids looking up at me, all dirty and sweaty, because it was a hot day and I thought, ‘What are these smugglers thinking?’” – Supervisory Border Patrol Agent Kenneth Kroupa, U.S. Customs and Border Protection. [Source: CBP]

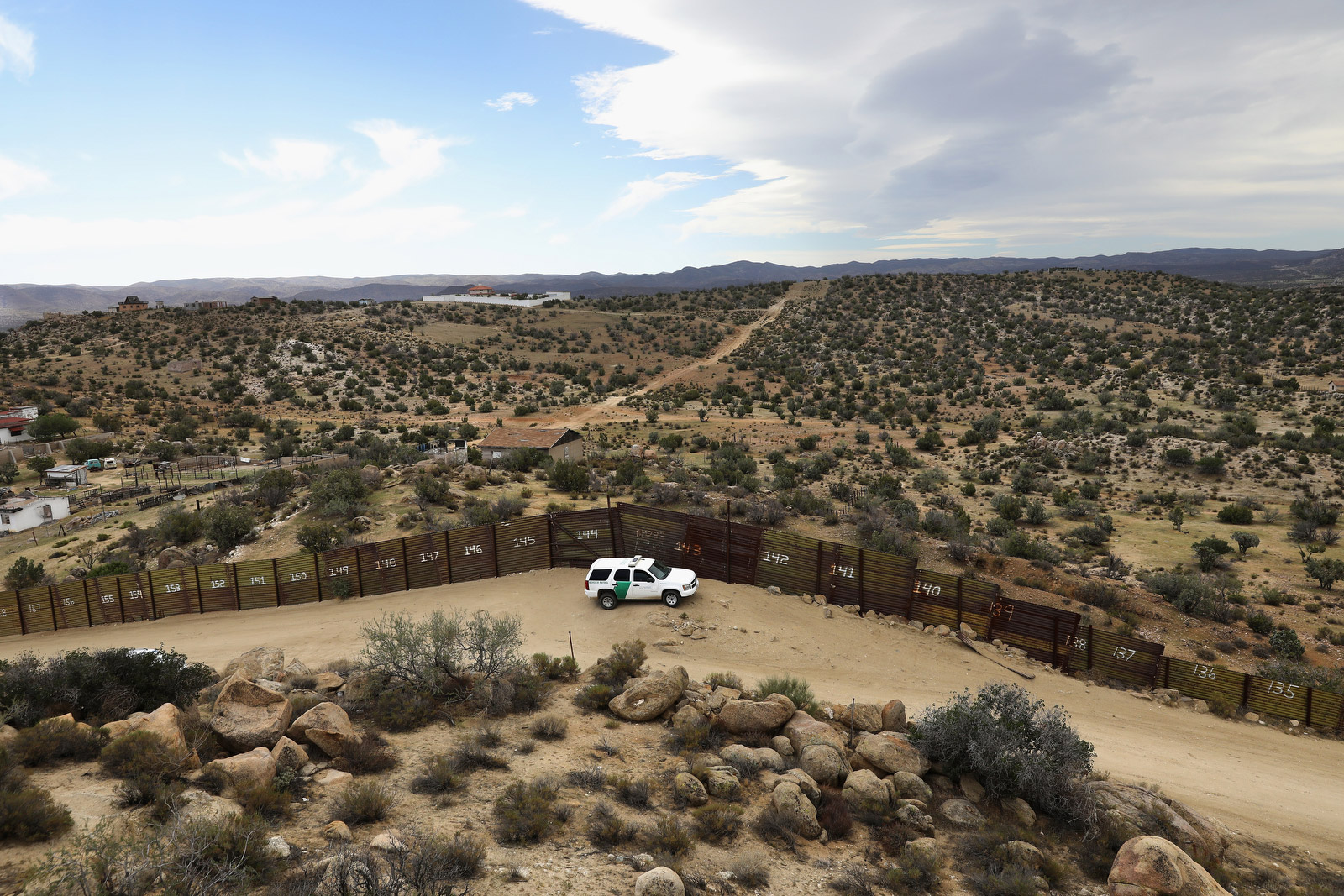

Even a cursory glance at US news will show the 2,000 miles from the Pacific Ocean to the Gulf of Mexico remains one of the most politically charged boundaries in the world.

However, this isn’t new. The history of the US-Mexico border shows this has always been No Country For Old Men.

Only in the earliest days of the borderlands were they a relatively fluid space. Families and economies overlapped until the region hit the 1850s. Over the course of this decade, the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo and Gadsden Purchase drew a line through communities that had long coexisted, intermarried, and traded. No longer were livestock, alcohol, and goods swapped back and forth without regard for jurisdictions drawn up hundreds of miles away in Washington. The people in what was now California, Nevada, New Mexico and (crucially) Texas had become Americans. The modern borderlands – the place we see in incendiary headlines or Cormac McCarthy novels – had been born. The borderlands were now defined by one thing: what (or who) can cross over.

By the 1920s, the violence and upheaval of the Mexican Revolution started to push people and weapons across the border zone, and the demand for guns in Mexico was equal only to Prohibition-era Americans’ demand for illegal booze. Bootleggers had made the borderlands a hub for the “vice economy”, shot through with liquor production, bars, casinos and illicit trade. With this came the first federal enforcement crackdowns, as US authorities struggled to control the surges and flows of this region’s new lifeblood: smuggling. As time passes, this will never change.

Liquor was a key commodity, but people provided more lasting value as contraband. A hundred years passed since the Gadsden Purchase when FDR’s Bracero Program legalised temporary Mexican labor in the U.S. Yet by this time, human smuggling had become as ‘normal’ as it could ever be. The federal government responded with operations whose shocking names recall a hundred-year history of anti-Mexican racism, brewing since the early days. Photographs are published of human beings packed into trailer cages, humanitarian abuses with echoes of crises half a century later.

“Q: So to be, to put a finer point on it, do you see U.S. employers, specifically, as clients, indirect clients of the smugglers that you spent seven years with?

A: Absolutely. 100%. They benefit from it daily. They need it.” – Interview with Jason De León, Executive Director at the Undocumented Migration Project, Professor of Anthropology and Chicana/o Studies at UCLA. [Source: WBUR]

Then, drugs. The marijuana - and later, cocaine - booms in the 1970s and 1980s forged the modern-day battleground between federal enforcement and increasingly powerful cartels. Measures like Operation Gatekeeper were no longer framed as purely immigration control, but open attempts to cut off the raging pulse of smuggling networks. Each wave of smuggling redefined how the U.S. approaches its Southern border, and the chaos of the 21st century has created a militarized enforcement zone.

Sites of horse patrols and ad hoc checkpoints now bristle with post-9/11 fences, floodlights, hi-tech monitoring systems, anti-climb devices. If the borderlands have a capitol, it’s San Diego-Tijuana: the busiest land border crossing in the Western world.

In 1855, this was a frontier valley, scattered with the adobe ranchos of blended Mexican-American families, surrounded by open land and the sound of ranch animals, the creak of wagons, dry wind across the hills. Those families wouldn’t recognize 1925’s American tourists, casinos, rife prostitution, illegal liquor and racetracks, a symbol of a border where “anything goes”. They also wouldn’t recognise the border town of 2025.

Today’s Tijuana is a sprawling metropolis of over 2 million people, fused economically and socially with San Diego in the States. Both sides rely on maquiladoras (factories for global manufacturing), tourism, medical services, cross-border trade - and, below the surface as always, the smuggling of people, drugs, weapons, luxury goods and even eggs. Thriving tech start-ups and booming craft breweries on one hand; cartel violence, fentanyl and methamphetamine, migrant camps, and fortified border infrastructure on the other. San Diego–Tijuana is a borderland microcosm.

On the American side, it’s down to U.S. Customs and Border Protection to keep the peace.

“Some say when you do it for a long time, you get numb to it. I don’t believe that at all… We want to get the smuggler who did this...” – Supervisory Border Patrol Agent Oscar Joanicot, U.S. Customs and Border Protection. [Source: CBP]

In 1925, a tax collectors, chasing stray cattle or untaxed liquor; by the mid-twentieth century, chasing bootleggers, labor recruiters, and marijuana couriers; then, in the shadow of 9/11, something closer to a soldier, stationed in a watchtower, scanning screens rather than patrolling the frontier like a cowboy. Still, the job remains the same as it was in the nineteenth century: to decide what, and who, is allowed through.

Most CBP officers are interested in disrupting the familiar rhythms of border smuggling. However the same officers tasked with fighting back can be tempted to play along. Taking bribes, waving through shipments, or tipping off cartels about patrol schedules aren’t a new story. These are crimes as old as smuggling itself. However, one way of investigating them is better suited for the 21st century border: open-source intelligence with OSINT Industries.

Meet Luke Harold, Border Journalist.

“Federal authorities, particularly law enforcement agencies, are not typically forthcoming with crucial details that help tell a story. OSINT is a crucial way to gather facts that would otherwise go unnoticed and unreported…” – Luke Harold, Journalist. [Source: OSINT Industries]

Luke Harold is a journalist resident in San Diego. Writing for multiple outlets and newspapers across the Los Angeles and San Diego area, Luke reports mostly on “the border, immigration, and notable cases in California's federal and state courts”, including mapping border complaints - and covering CBP corruption. OSINT is a key part of his investigative strategy, and OSINT Industries his preferred tool.

In Luke’s work, he reviews documents from all across the US federal court system, with drug and human trafficking appearing as everyday topics. Via Substack, Luke’s border mapping project is an ingenious use of publicly-available information to record smuggling incidents by state, type of illicit goods and case type. Coordinating open-source documents are linked, alongside profit numbers for the smugglers involved: from oxycodone in Oregon to carjacking in El Cajon. However, Luke’s heat map of incidents explains why his work centers primarily around the San Diego-Tijuana region.

As part of his CBP corruption project, Luke manually compiles data on wrongdoing by border patrol officers revealed in publicly-available federal documents. Electronic communications are a backbone of smuggling operations, and investigations. Federal authorities will file multiple search warrants for electronics in each case, and this means details on suspects are often published in court files.

At the 2024 Investigative Reporters and Editors conference in Anaheim, Luke first heard about OSINT Industries. Now he uses our tool to enrich his findings on suspects and convicts, “searching those emails and phone numbers that are subject to those search warrants for any additional information that federal authorities do not know or have not shared publicly.” Using OSINT, Luke can go further with publicly backgrounding smuggling suspects than even the authorities themselves - increasing much-needed transparency around the Southwestern states’ oldest hot-button issue.

Earlier this year, Luke’s CBP mapping project brought to his attention charges filed against agents allegedly working with human smugglers.

Two agents had been previously charged, and this had been widely reported. Court documents listed evidence had come from arrests of smuggled people, “highly suspect crossings” and a message thread on an alleged smuggler's cell phone including a contact "Farli USA" who shared his work shift times. However, months later, a newly unsealed grand jury indictment changed things.

Unexpectedly, alongside Farlis Almonte and Ricardo Rodriguez, the two known alleged smugglers, was a third named CBP officer: Kairy Stephania Quiñonez. Little was being shared publicly about her. Case files on PACER showed a fourth defendant, Jaime Torres Jr., was named in the indictment too. The U.S. attorney’s office had never mentioned these names in their May 6 press release.

Could OSINT Industries shed some light on these subjects?

Gatekeepers Become Enablers: CBP Officers Accused of Smuggling

“This case is one of many involving CBP officers charged for working with either human smugglers or drug traffickers, as I’m actively working to document…” – Luke Harold, Journalist. [Source: OSINT Industries]

Indictments and press releases suggest the crooked officers’ scam at San Ysidro Port of Entry allegedly ran as follows.

Coordinating beforehand - and accepting bribes for their services - the involved officers would let vehicles with migrant passengers pass through their border check lanes without inspection. Thanks to these officers sharing their lane assignments and hours via message threads, smugglers knew when ‘friendly’ CBP officials were manning the primary inspection booths. Sometimes, co-conspirators used code words to gain access.

Meanwhile, the defendants would log a false report with the wrong number of occupants on the Transportation Enforcement Communications System, a border-crossing database known as “TECS”. With the smuggled passengers invisible on the records, they could pass undocumented into the USA.

As a result of their alleged actions, the officers involved caught charges of receipt of bribes by a public official. “In exchange for money”, the indictment states, “they failed to enforce the immigration laws of the United States by allowing vehicles with undocumented immigrants to enter the United States”. Considered a particularly grave offence in the current climate, their case is being prosecuted by Assistant U.S. Attorneys Francisco Nagel and Bianca Calderon-Peñaloza.

As always, Luke turned to OSINT Industries for “a closer look” at the defendants. Career-focussed modules like LinkedIn could clarify the journey these officers took from border ‘soldiers’ and defenders of smuggling victims, to charges of assisting smugglers themselves.

First, Ricardo Rodriguez. According to a court filing by his attorney, Rodriguez was “a participant in the National Guard” from 2012 to 2023. Luke’s work confirmed that he has no previous criminal record, and worked for TSA before joining U.S. Customs and Border Protection. Since January, OSINT Industries results suggested he had quit his job and now resides with his girlfriend in Mexico.

Second, Farlis Almonte. Almonte, as his attorney suggested, didn’t have a criminal history either. Luke’s OSINT work confirmed that he worked in private security, before becoming a federal protective services officer for the Department of Homeland Security in 2015. Six years ago, he began working for CBP; he had been stationed in Arizona and Minnesota before relocating to San Diego in 2023.

Lastly, the mysterious Kairy Stephania Quiñonez. An OSINT Industries search suggested she worked briefly for the city of Baltimore as a visitation monitor, checking in with victims of domestic violence and advocating for victim protection. She began her work with CBP in 2021. Also, for a time, she had taken up Portuguese on Duolingo.

These small biographical notes on each of the accused highlights the importance of Luke’s backgrounding work. None of these suspects were career criminals. In fact, their professional lives were ordinary, unremarkable or even laudable before their arrests. Quiñonez’s indictment now seems particularly striking. She must have been aware of the complex human reality of illegal crossings, and the trauma of an illicit trade that recasts people with dreams of a better life as a tradable commodity. What’s more, Portuguese would allow her to communicate with the undocumented population who speak it.

That someone with a background in victim protection and advocacy can allegedly turn to facilitating smuggling exposes both the vulnerabilities within border institutions, and showcases the enormous pressures and temptations of the borderlands. If smuggling is the current of the border, it's powerful enough to pull even those sworn to stop it into its flow. With OSINT industries, Luke exposed to the public that these suspects’ motivations are far from clear-cut.

The Border Online: OSINT Tools Meet the Old Frontier

Border enforcement has also moved with the times. Digital improvements in the way data is processed, and now OSINT helps CBP to investigate how the Tijuana–San Diego border operates. GEOInt on satellite imagery can expose distinctive patterns near warehouses or vacant lots that suggest tunnels, drones, or semi-submersibles; unusual surges in public data can correspond to drug shipments slipping through; and most importantly, social media is both a place for “coyote” advertisements on TikTok or Facebook and for locals to post real-time reports of violence, tunnel discoveries, or migrant staging points.

“It was a more tedious process trying to search phone numbers and emails for potentially useful information. OSINT industries provides a more centralized and convenient approach…” - Luke Harold, Journalist. [Source: OSINT Industries]

Journalists like Luke are wading through the same data flows, and tools like OSINT Industries streamline what once required hours of trawling through disconnected records. U.S. federal indictments are fuel for CBP smuggling busts, but also for keeping the public finger on the border’s pulse. In Luke’s hands, OSINT is a way to bring transparency to the inner workings of his region (and an American crisis) beyond the headlines. That’s why we at OSINT Industries are proud to assist reporters like Luke in doing what they do.

Border smuggling is as old as the border itself. In another hundred years of cyber development, the borderlands might be unrecognizable again. Yet with OSINT in play, there is always somebody watching. This online world is just a new frontline in the age-old struggle: over what - and who - will be able to slip through.

To find out more about Luke Harold’s work, check out:

Start your free enterprise trial

Get Free TrialReveal what's behind any contact, instantly.

We want to hear your story!

Inspire Others

Educate about what OSINT can do.

Positive Publicity

Share your success with the world.

Support #OSINT4Good

Be part of the OSINT story.