Try the world's most popular OSINT platform for free. Elevate your enterprise investigations with unmatched accuracy.

Scam Victims: Inside the Global Crime Network Behind Fake Jobs — and the OSINT Exposing It

Those annoying fake WhatsApp job offers? @akaclandestine’s OSINT ties them to a global atrocity.

‘Many scammers are victims themselves… The entire office would sing an ominous chant, “You make money, I’m rich, you’re rich, we’re rich. You don’t make money, I die, you die, we all die”...’ – Secunder Kermani, Foreign Affairs Correspondent, Channel 4. [Source: C4]

The typical scam used to promise us millions from a dead foreign prince. It’s a symptom of today’s world that scammers now promise us a stable job. A cousin of pig-butchering operations, ‘job-message’ scams originate in Southeast Asia. An epidemic according to the FTC, they offer easy online tasks and quick pay as bait for increasingly desperate (and underemployed) Westerners. To establish credibility, job-message ‘recruiters’ will say they work for major providers of insecure work like Amazon, TikTok or YouTube. They may even send small initial payments, as if the magically steady work you’ve been offered by an anonymous possibly-AI person via text message really does, against-all-odds, exist.

Soon, however, it’s too good to be true. Victims have to pay an “unlock fee” to withdraw their earnings. If the transfer is made, your friendly new ‘recruiter’ disappears; leaving you out of a job, and out your money.

“What began as a regional crime threat has become a global human trafficking crisis…” - Jürgen Stock, Interpol Secretary General. [Source: TIME]

But where does that money go? OSINT has long attempted to answer this question, and we largely have the answer. It’s uncommon for the money job-message scammers hoard to stay in their victims’ home country where their victims live. Ill-gotten money has to be scrubbed clean, and the process is typical: a chain of intermediaries, money mules, shell or front companies, transfers disguised as routine business activity. Cryptocurrency offers an easy way to obscure the origin and destination of funds by the time they get to their new Southeast Asian home. Here, large-scale scam operations are the main way organized criminal networks rake in the millions - and the bosses aren’t the ones sending DMs.

It’s easy to hate scammers. The reality is many are as victimised as those they con.

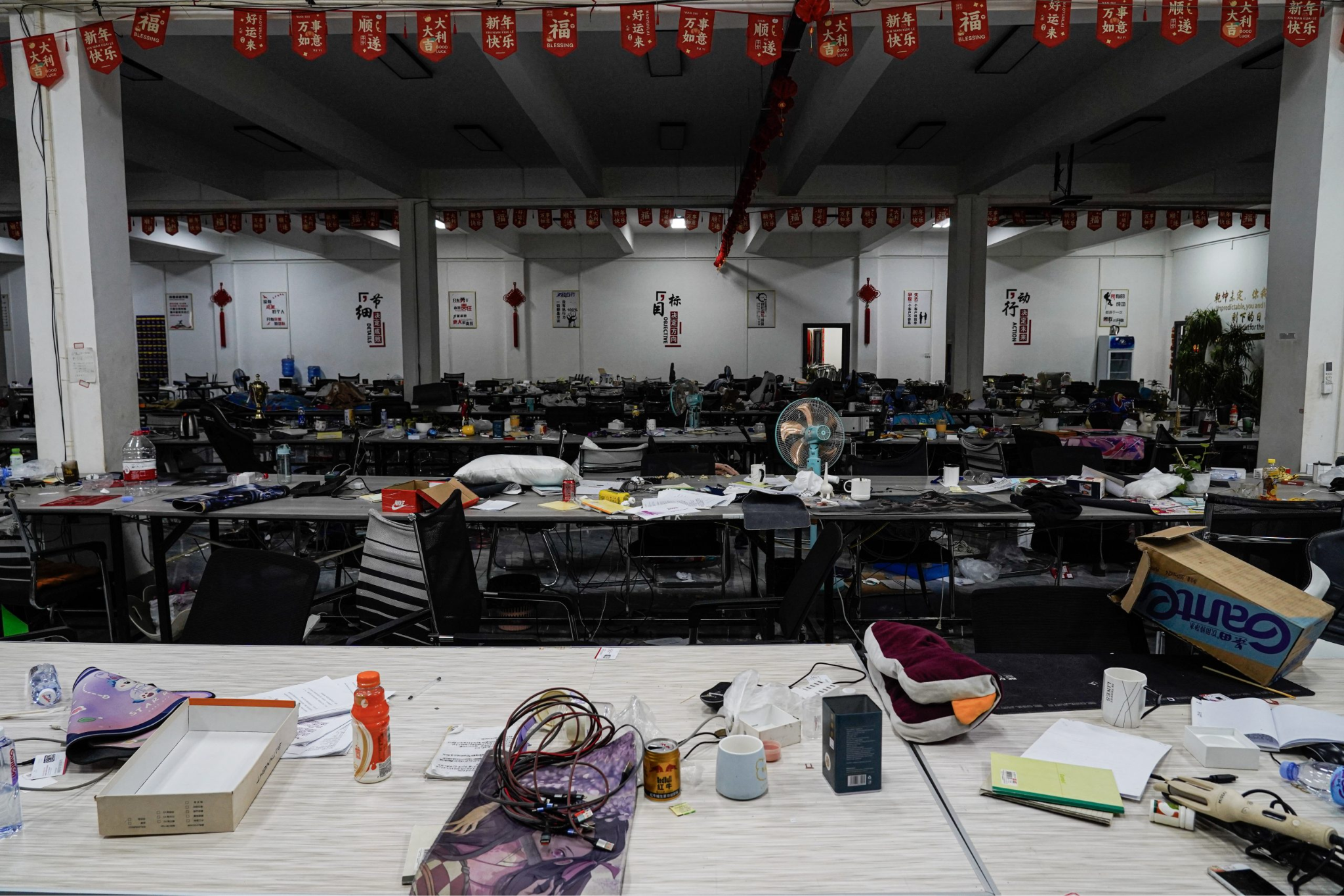

Further research now shows that a large portion of these illicit funds pours into maintaining an essential part of the business: the fraud center or ‘scam farm’. True to their name, these enormous criminal-run fraud compounds are built like battery farms, where often-trafficked ‘recruiters’ work en-masse; without their passports or personal freedom, and under threat of torture. These compounds look like legitimate repurposed office-blocks, dormitories, casinos or hotels. In reality, they’re sweatshops for scams.

Back in the ‘90s, 80% of all New York’s heroin came from the ‘Golden Triangle’: China, Cambodia and Laos. After eradication programs and the U.S. War on Terror handed the opium crown to Afghanistan, everything changed. Public, open, and often politically-sanctioned, the ‘scam state’ is now estimated to be one of the main economic drivers of the Mekong region.

“These are massive pieces of infrastructure, set up very publicly. You can go to borders and observe them. You can even walk into some of them…” – Jason Tower, Global Initiative Against Transnational Organised Crime. [Source: Guardian]

The UK’s Channel 4 reported on a raid occurring on Myanmar’s notorious scam farm, ‘KK Park.’ After a junta, up to 20,000 trafficked and brutalised ‘workers’ had already disappeared. Still, what they found was dystopian.

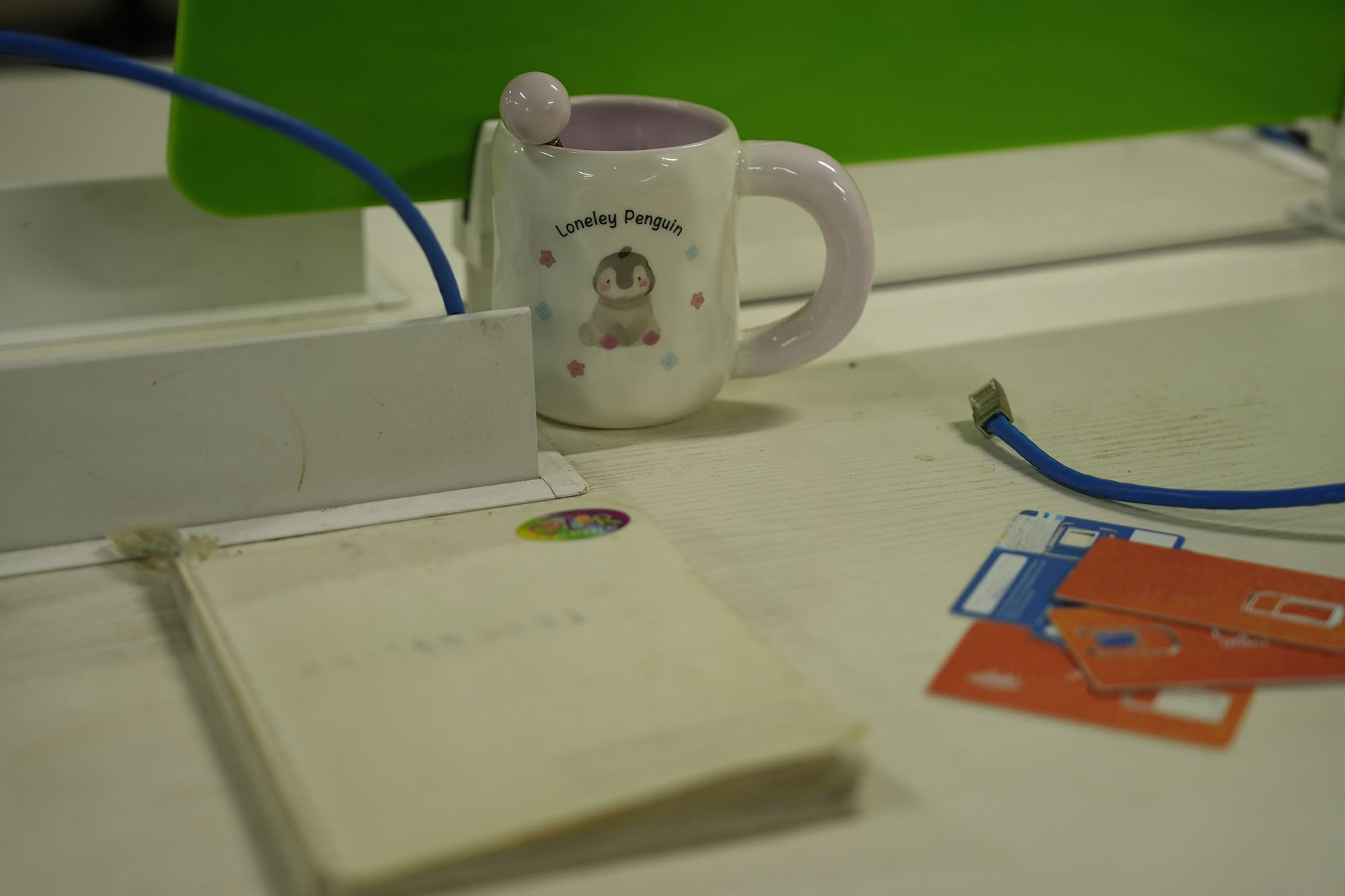

Hundreds of computers and thousands of mobile phones. A fake-cosy ‘living room’ for video calls with targets, complete with hollow plastic books on the shelves. Notepads where ‘recruiters’ had tried to brainstorm ideas for convincing Western-style conversations, to remember “which river in Miami is best for fishing?” Behind the motivational slogans that lied “all your money go home” was the room of aluminium ‘torture booths’.

Those scammed out of money are victims, taken advantage of while they’re suffering their own pains of grief, depression or loneliness. Still, Channel 4 correspondent Secunder Kharmani found Chinese victims of the scam farm’s modern slavery crowding around a ‘recruiter’ with “awful scars on his back”. Abraham, an Ethiopian software engineering graduate, secured what he thought was a “sales job in Bangkok”. Instead, he was trapped in Myanmar, “working 14 hour shifts, with orders to bring in at least $20,000 a month” - or else.

If the fear didn’t keep Abraham from sleeping,“guilt” did. Former real estate agent Rachel Yoong relayed a similar story. The casino job she was offered would have paid even more per-month than her very professional role back in Malaysia. She didn’t count on a new life on the Myanmar-China border, where armed thugs and sleeping eight-to-a-cell were the norm. Like Abraham, Rachel was expected to scam American victims for 17 hours each day using a catfish profile. Failing to meet quotas would mean beatings, electrocution or worse.

“I saw three people die,” says Yoong. “One coworker jumped from the roof; two others were pushed…” – Rachel Yoong, real estate agent and scam-trafficking victim. [Source: TIME]

In order to run ‘job-message’ scams, organized criminals run a job scam that’s unfathomably worse. As well as trafficking, verbal humiliation and physical beatings, Interpol reports scam farm ‘workers’ are regularly subject to sexual assault, rape, and even forcible harvesting of organs.

How, you may ask, if they operate out of Myanmar or Laos, are job-message ‘recruiters’ able to conduct extensive, convincing conversations in fluent English, German or Portuguese? Even countries like China and Indonesia place in Low Proficiency bands for English, and far lower for other Western languages. Yet job-message scams - including successful catfishing - are a worldwide plague.

The answer is what necessitates kidnap. The raid on KK Park found 1,500 trafficked people from about two dozen nations. In many scam farms, you’ll find citizens of South America, East Africa, and Western Europe enslaved. Rachel Yoong’s escape involved convincing bosses to ‘sell’ her out of her 10-story concrete hell to another scam center; here, because she spoke multiple languages, she was able to act as a supervisor.

With so many international reverberations, OSINT investigators who began looking into WhatsApp scams are starting to discover the truth behind this chain of victimization.

‘Towards the end, I was beaten 13 times in one day. I just prayed and prayed while they beat me. I was forced to call my parents and ask them to pay $7000 for my ransom, which was the cost of the hospital bill… I said to my managers “just kill me.”...’ – Susan*, survivor of a Myanmar scam farm. [Source: UNODC]

The shrapnel left behind by the chaos of a scam farm includes recycled phone numbers, reused scripts, identical payment flows, cloned websites, burner domains, corporate records scattered across multiple jurisdictions. These are a lifeline for understanding a crime economy operating across continents. They show that a WhatsApp job message pinging in São Paulo is not an isolated act of petty fraud. It’s a fragment of a global criminal atrocity.

The Targets: Xizhangpeng Hao and Sun Chunyang

The human stories emerging from Southeast Asia explain the brutality of the scam farm system. OSINTers like @akaclandestine are beginning to explain its architecture.

@akaclandestine is a world class OSINT investigator, specialising in security, OpSec, Humint, infosec, threat research and intelligence. His outstanding work has landed his name in the Cert-Eu, Gruppo TIM, Utrecht University, Basf, Bosch, Vivaldi, Philips, Bayer and UNESCO Halls of Fame.

He’s brought down Brazilian scam networks and pedophile chatrooms before, sharing his stories with us of how OSINT Industries helped him do so. He reached out again to do the same thing this time, on a bigger case than ever.

His latest targets: Xizhangpeng Hao, and Sun Chunyang.

Both are Chinese nationals operating in Brazil. Both are attached to a map of criminal infrastructure: 4 front companies, money-mule accounts, multiple phone numbers, 13 addresses. Both have connections to several Brazilian government investigations.

Most importantly, they’re players in a US$64 billion-a-year global scam industry controlled by Chinese syndicates - and operating fraud centers in Myanmar, Cambodia and Laos. Their Telegram “task scams” have defrauded thousands of Brazilians, and even trafficked Brazilian citizens into their nightmare.

@akaclandestine reached out to us to share his story of how an investigation into Brazilians losing money went global, and how OSINT Industries helped build a OSINT report that charts it all.

The Bait: How Fake Job Scams Lure Victims In

“Congratulations, you have been selected for an online part-time job, 5000BRL per day, contact me. WhatsApp: +[62]*****. Add a manager and earn a 12 real reward…” – Message received by Brazilian scam victims. [Source: @akaclandestine/OSINT Industries]

What first drew @akaclandestine in was the scam. He set out to unpick just how people across the country were losing money to the promise of a job.

The process begins, as usual, with unsolicited messages offering tempting pay for absurdly simple online tasks. This time, Indonesian +62 numbers - impersonating brands like Amazon, Google, Shopee and YouTube - offering R$200-5,000 a day for likes and reviews. This scam favors moving targets to 500-5,000 member Telegram groups, where a ‘receptionist’ (aka ‘recruiter’) collects personal data and Pix keys. Newcomers can’t speak in this chat, and fake Pix screenshots create enough FOMO to get targets signed up for ‘VIP tasks’, with the attendant R$120 to R$300 investment quickly returned with profit to solidify confidence. A personal ‘mentor’ then enters the picture. Psychologically, their purpose is to encourage the leap into progressively larger investments and increasingly “exclusive” groups. When the deposit’s big enough, the victim’s account suddenly ‘freezes’. Time to buy an ‘unlock key’ - not that it’ll work.

Rinse and repeat, until the victim refuses to play… or runs out of money.

“There was an error processing your task. You need to deposit another R$2,000 to fix the system…” – Message received by Brazilian scam victims. [Source: @akaclandestine/OSINT Industries]

From untangling this modus operandi, @akaclandestine was left with a few leads for OSINT: a certain scam methodology, those Indonesian +62 numbers, and repeated reference to the same CNPJ records in victim complaints. He chose the latter.

Following this corporate trail led him to his first breakthrough. The two companies popping up again and again were Cash Pay Meios de Pagamento LTDA (CNPJ 48.689.840/0001-30), founded in Sao Paulo in 2022, and Golden Cat Processamento de Pagamento LTDA (CNPJ 52.348.833/0001-41), founded in the next year at the same address as Cash Pay. Both companies listed the same administrators, Xizhangpeng Hao and Sun Chunyang.

These companies were on Brazilian authorities’ radar. As part of Brazil’s landmark Congressional Parliamentary Inquiry (CPI) on football match-fixing, the Chamber of Deputies issued formal summonses for individuals named Sun and Hao as part of REQ 34/2023 (CPIFUTE). Further filings from that CPI include financial-tracing requests which list Cash Pay as a payment intermediary under examination. Again, in Operation Desfortuna, the 2025 Brazilian Federal Police action against a R$810 million illegal-gambling influencer scam, Cash Pay showed up as a financial conduit for illicit transfers.

Cash Pay and Golden Cat also used identical phone numbers and emails across both companies: (51) 3311-90** and contato@cashpay[.]com.br. Major red flag. This was a job for OSINT Industries.

The Operators: How OSINT Traced the Men Behind the Message Scam

Now @akaclandestine knew the scam’s culprits, OSINT Industries could help him on a deep dive into their activities. Queries on the two men’s names and initial email address returned massive data.

‘Xizhangpeng Hao is a “ghost” in the digital world, suggesting high- level criminal sophistication…’ – @akaclandestine, OSINT Investigator. [Source: @akaclandestine/OSINT Industries]

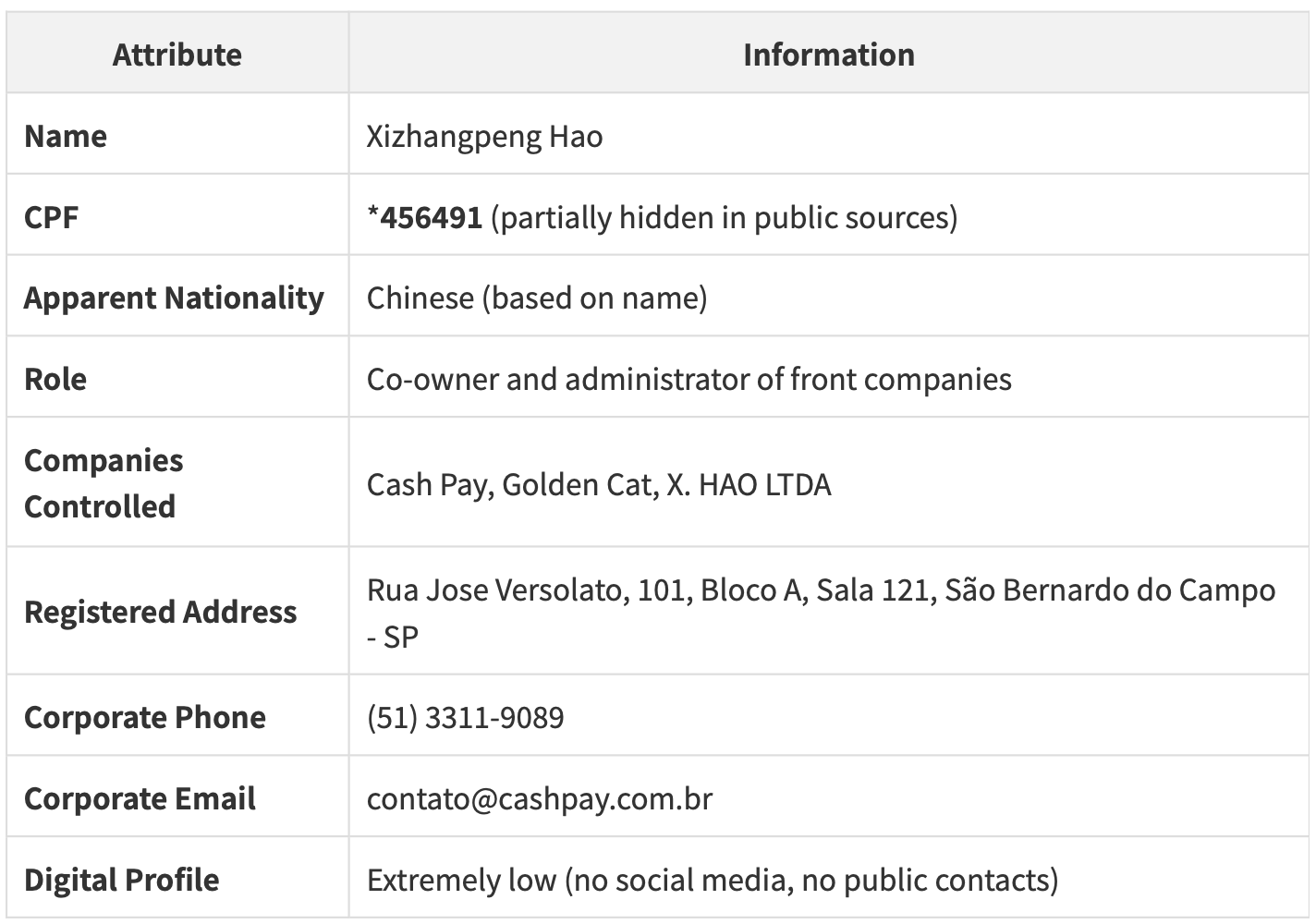

First, Xizhangpeng Hao. OSINT Industries revealed:

533 detailed modules found

447 unique names

329 unique usernames

230 unique IDs

42 locations

89 creation events

However, the data was fragmented. Not only was Hao a common name, but the Xizhangpeng Hao related to these two companies maintained an extremely low digital profile. He had no obvious social media, no public email, and no personal phone numbers. According to @akaclandestine, this level of operational security is suspicious in itself, ‘consistent with experienced criminal operators who deliberately avoid leaving digital footprints.’

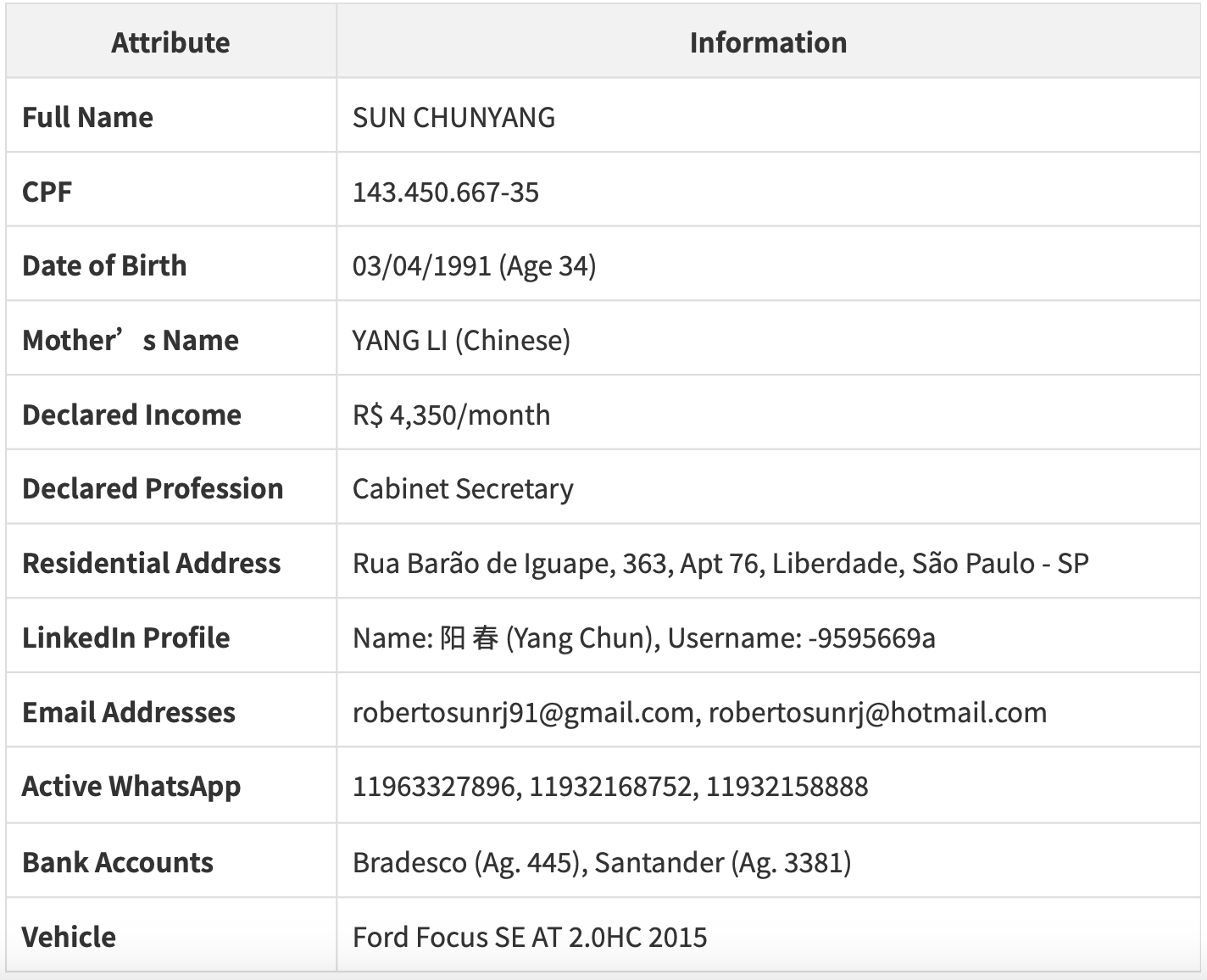

Next, he turned to Sun Chunyang.

A hypothesis emerged: if Sun Chunyang was operating in Brazil, he likely had Brazilian email addresses and social media accounts.

Again, many modules, usernames and IDs appeared, but they were also fragmentary. One email, however, recurred with regards to Sun: robertosunrj91@gmail[.]com.

This email returned the LinkedIn profile ‘阳春’ (Yang Chun), with a distinctive username that had also appeared when searching ‘Sun Chunyang Brazil’: -a9595669a. The variant robertosunrj@hotmail[.]com returned accounts on Instagram, Microsoft and Google Maps, active days before and with locations listed in Brazil, and an Apple phone number hint. Breach patterns matched well on both.

This confirmed that robertosunrj@gmail.com and its variants likely belonged to Sun Chunyang. @akaclandestine theorized Sun used a ‘dual identity strategy’, with a Chinese display name (“阳 春”) for Chinese networks, and a more Portuguese-sounding email (“roberto”+“sunrj”) to appear local in Brazil.

A massive 15 phone numbers associated with Sun. OSINT Industries showed only 3 ‘high priority’ numbers were active on WhatsApp - like Hao, Sun had compartmentalized his identity. The other numbers were active on Telegram.

For Brazilian OSINT, a CPF lookup is an essential next step in personal investigations. A CPF, or Cadastro de Pessoas Físicas, is Brazil’s national tax identification number, similar to a Social Security Number in the US or National Insurance Number in the UK.

Sun had 13 addresses, 8 in Rio de Janeiro and 5 in São Paulo. These were the same addresses, deliberately recorded up to four times in multiple formats for obfuscation. @akaclandestine was able to confirm a Liberdade address as a primary residence, splitting the address data into two groups:

São Paulo (Liberdade): Primary residence, Rua Barão de Iguape 363, Apt 76, Liberdade. Liberdade is São Paulo’s Chinatown, strategically chosen for integration with the Chinese community.

Rio de Janeiro (Maracanã, Vila Isabel, Centro): Multiple operational addresses, likely safe houses or mail drops.

It seemed clear that Sun lived in São Paulo, but operated from Rio de Janeiro. Looking up Sun Chunyang’s CPF also gave @akaclandestine the following:

DOB: 03/04/1991 (age 34)

Mother: Yang Li (her Chinese name)

Declared income: R$ 4,350

Profession: Cabinet Secretary

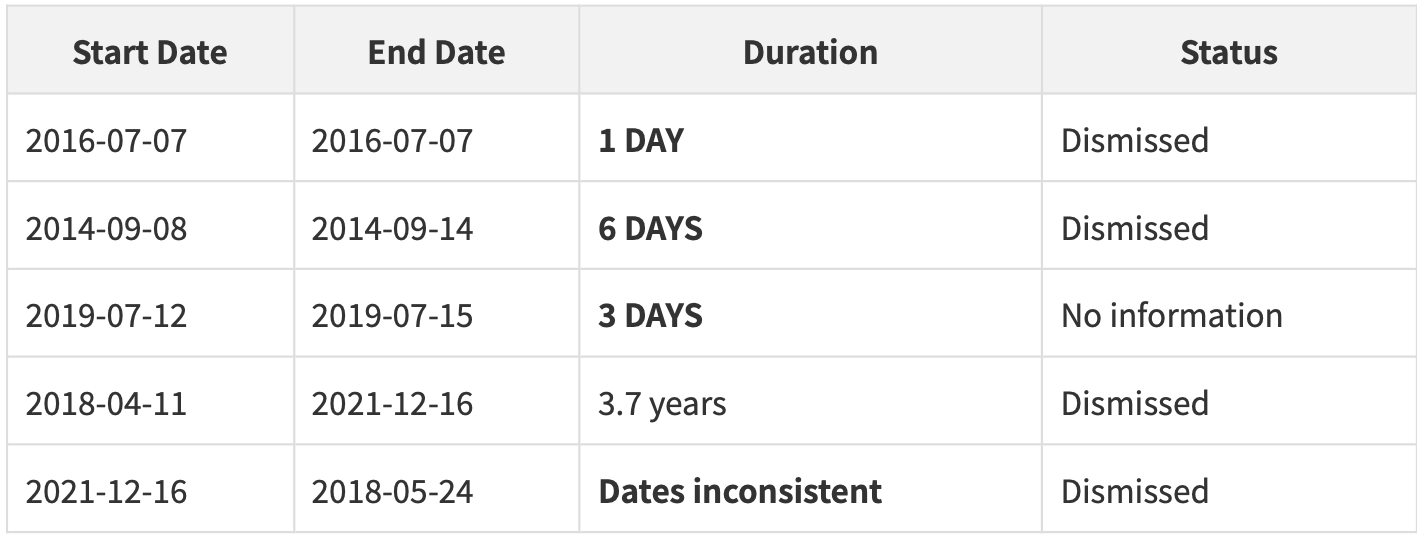

The Chinese name listed for Sun’s mother confirmed his status as a first-generation Chinese immigrant. What’s more, such a low declared income was incompatible with Sun’s operations - Cash Pay alone reported a R$1.5m value. This disparity became clearer after scrutinizing Sun’s employment history, which revealed a ‘shocking’ pattern:

‘No legitimate company hires and fires an employee in 1 day. These ultra-short employment periods are strong evidence…’ – @akaclandestine, OSINT Investigator. [Source: @akaclandestine/OSINT Industries]

Not only do the end and start dates make no sense, but whatever they were, these micro-stints of employment meant trouble. For money laundering, short-term employment can justify fund transfers. For shell company operations, temporary activation of employment can facilitate specific transactions. For document fraud, a false employment history is a must - and for evading tax, Sun could have declared income from work that didn’t exist.

Sun Chunyang had tried his hand at many kinds of career-themed con.

Furthermore, Sun had one stint of ‘legitimate’ employment: at H. Stern Comércio e Indústria S.A., a luxury jewelry company, starting May 31, 2023. This looked highly anomalous for a man usually fired after about three days.

@akaclandestine had three theories. Holding a legal job while running criminal operations on the side (‘less likely’, to be polite); money laundering via luxury goods purchases’; or CNPJ fraud on the H. Stern’s legitimate tax ID. He would have to check with the company and verify Sun’s employment to be sure.

Another quirk of CPF data is the inclusion of a detailed consumer behavior profile. Combined with SOCMINT on OSINT Industries, Sun showed:

Confirmed Interests/Behaviors:

✅ Tourism, ✅ Interest in luxury goods, ✅ Cable TV subscription, ✅ Broadband internet, ✅ Mortgage credit, ✅ Online shopping, ✅ Personal credit, ✅ Investor profile, ✅ Private healthcare (Qualicorp), ✅ Private pension plan, ✅ Internet banking usage, ✅ Credit card ownership, ✅ Multiple bank accounts (+), ✅ Intensive internet usage, ✅ Airline miles redemption, ✅ Cinema enthusiast, ✅ Homeowner, ✅ Online gaming, ✅ E-reader ownership

Does not have:

❌ Payroll loan, ❌ Multiple credit cards, ❌ Health insurance, ❌ Life insurance, ❌ Home insurance, ❌ Post-paid mobile, ❌ Pre-paid mobile, ❌ Video game console

Sun was a ‘sophisticated financial operator’, avoiding any long-term commitments or paper trails while living a comfortable lifestyle. This was not somebody with a declared income of R$4,350.

The Syndicate: How Indonesian Numbers Lead to Scam Hell

‘With very high confidence, this operation is part of a Chinese transnational criminal organization operating from Southeast Asia with a money laundering infrastructure in Brazil managed by Xizhangpeng Hao and Sun Chunyang…’ – @akaclandestine, OSINT Investigator. [Source: @akaclandestine/OSINT Industries]

‘Job-message’ scams are not a Brazilian invention. Sun and Hao’s use of Indonesian (+62) phone numbers in their scam is deeply sinister.

It all made sense: the Indonesian numbers, the catfish profiles named Aline, Anastasia, Márcia, Victoria or Emily. Indonesia is a major hub in the ‘scam state’ ecosystem. Those operating scam center compounds will commonly use Indonesian SIM cards to avoid direct tracing to Myanmar, Cambodia or Laos. Perhaps the likes of Sun and Hao know their targets can read the news. Perhaps they don’t want us to be aware our victimizers might be victims too.

@akaclandestine notes that we know ‘Brazilians are among the trafficked workers, lured with fake IT job offers and forced to defraud victims in their native language’. It would explain why WhatsApp and Telegram messages from Sun and Hao’s scam involve relatively fluent Portuguese conversations, despite automated translation errors in scripts. Trafficked Brazilian ‘receptionists’ and ‘mentors’ will work from initial contact scripts machine-translated from Chinese. This leads to slip-ups like incorrect agreement and pronoun placement errors, inappropriate use of verb tenses, and use of expressions or idioms that make sense in Chinese, but not in Portuguese.

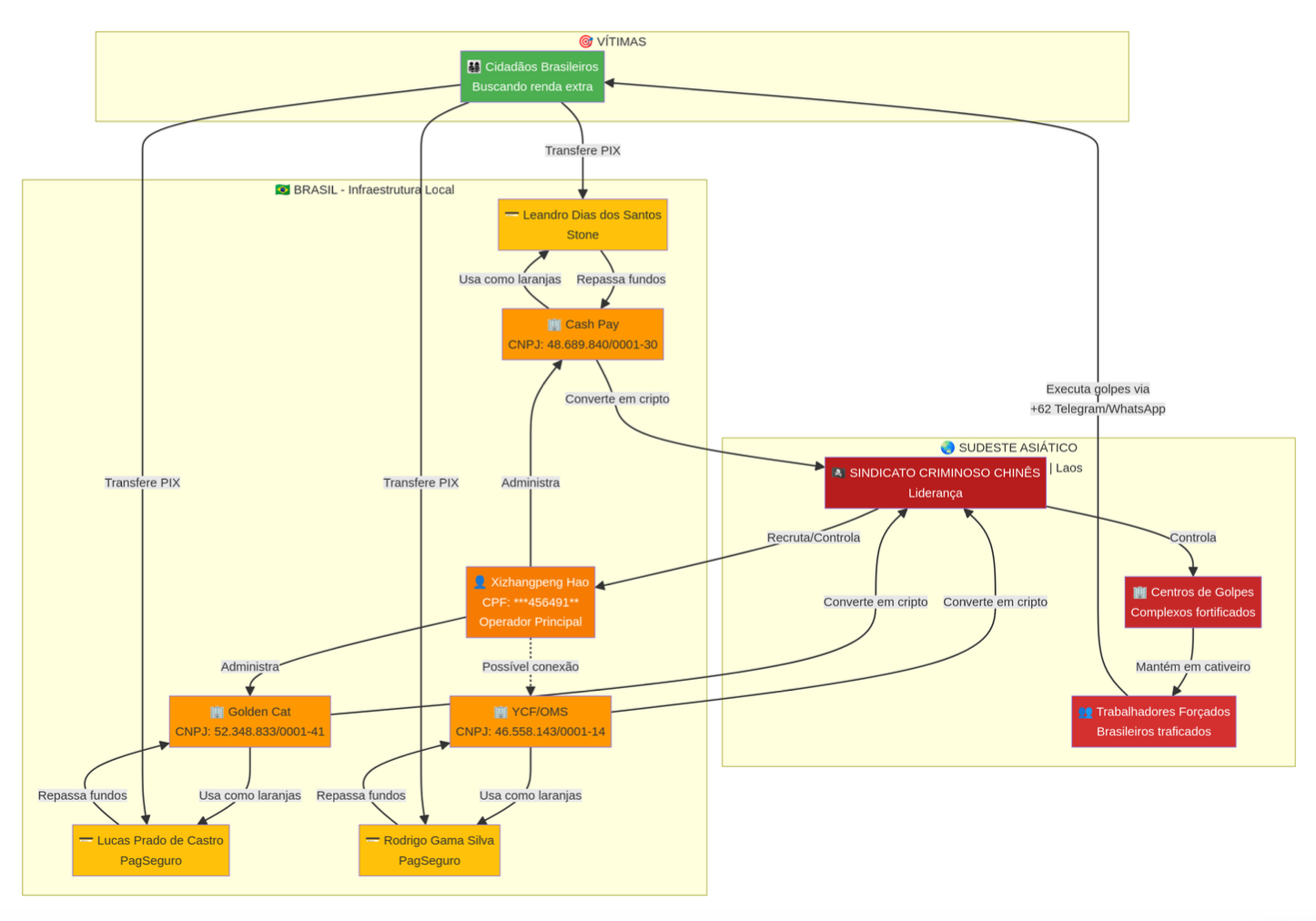

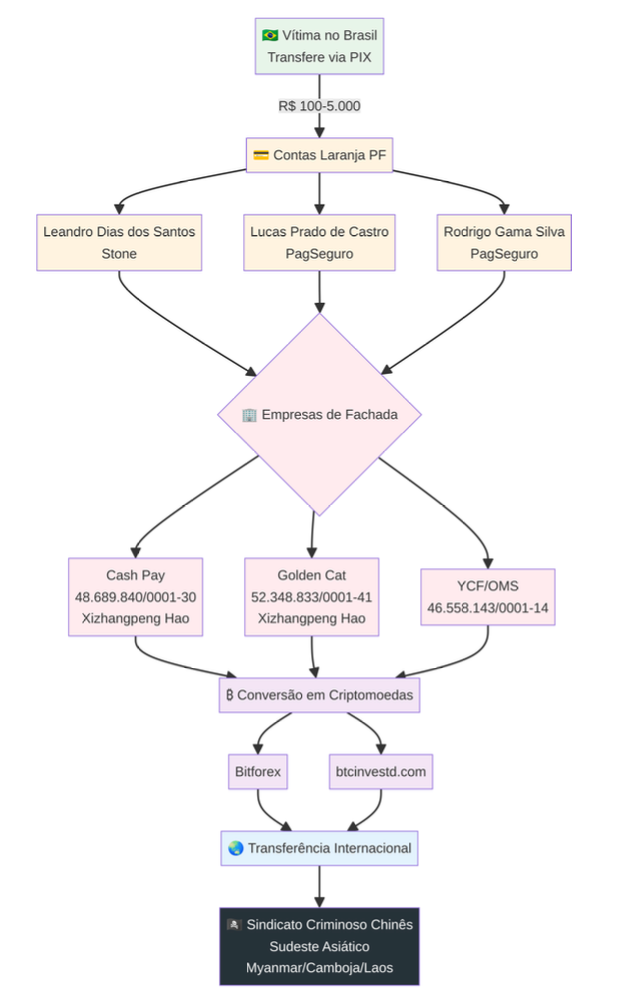

As he mapped the mechanism of the scam itself, @akaclandestine also used OSINT to delineate the architecture and methodology of Sun and Hao’s monster. This is how it works.

Level 1: Leadership

A Chinese syndicate operating from fortified compounds in SE Asia. Located in special economic zones on borders and protected by military and ethnic armed groups, they use forced labor and human trafficking to run scams. Trafficked Brazilians, Chinese, Indians, Filipinos, and Africans are held in captivity.

Level 2: Local Operators in Brazil

These men are responsible for company control and operational roles, and were the targets of @akaclandestine’s operation. They are operators, and not low-level participants. They are also potentially accessible to Brazilian authorities.

Xizhangpeng Hao (primary operator)

Sun Chunyang (secondary operator)

Level 3: Front Companies (Registered in Brazil)

These include YCF Shop/OMS, X. HAO LTDA, Cash Pay and Golden Cat. Hao and Sun are listed as administrators and owners. These are shell companies that will change their names to avoid scam complaints in which they are named. The latter are two supposedly independent companies sharing identical addresses, phone numbers, and email addresses, indicating centralized control. These companies have appeared in government investigations around illegal financial activity.

H. Stern, @akaclandestine notes, is a legitimate, renowned jewelry company. They are encouraged to investigate ‘highly anomalous’ connections that may suggest money laundering activities by Sun Chunyang via luxury goods.

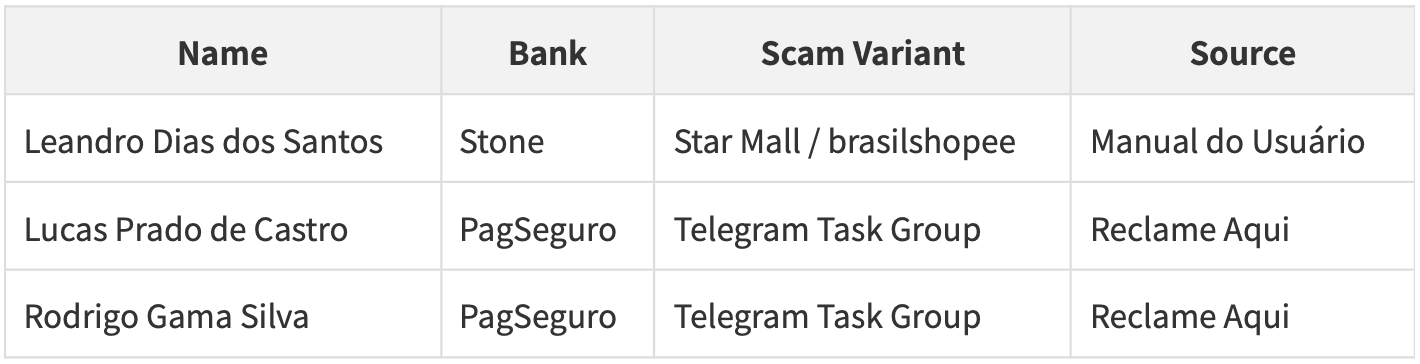

Level 4: Money mules

These are named Brazilian individuals that accept Pix payments, functioning as ‘financial mules’. They receive victim funds before transferring them to the front companies in the tier above.

These mules are key in the pathway @akaclandestine revealed, via OSINT, to route funds directly to Chinese syndicates that deal in human suffering.

The Brazilian victim pays the mule. The money mules transfer these funds to front companies. The front companies then convert the victim's BRL into cryptocurrency, through Bitforex and proprietary scam site btcinvestd[.]com, rendering it untrackable. From here, the money leaves Brazil. It reaches syndicate-controlled wallets in South East Asia. This is irreversible. There are no banking intermediaries, and international cooperation is unlikely.

This money pays compound operators, finances the infrastructure, bribes local authorities, and finally returns profits to syndicate leadership.

The Warning: How to Avoid Becoming a Victim

Job-message scams are built on the suffering of those coerced to run them. However, this doesn’t mean those who fall for them aren’t suffering too. US$75bn was lost to these scammers last year, and victims are left to pick up the pieces with often devastating results.

Not everybody can bite back at the architecture of a scam with OSINT Industries. Still, @akaclandestine shared with us the companies, individuals and numbers best avoided. In addition to the companies and accounts mentioned above, the following are best avoided:

Malicious phone numbers (DDI +62 incl.)

+62 857-6589-0735 (redirects to +55 33 8717-4435)

+62 857-2421-6537

+62 857-0133-1396

+62 857-2726-xxxxx

+62 813-3443-8801

Malicious Domains and Services

superorders93.com

btcinvestd.com

brasilshopee (variable domain patterns)

Money Mule Accounts (named)

Leandro Dias dos Santos (Stone)

Lucas Prado de Castro (PagSeguro)

Rodrigo Gama Silva (PagSeguro)

Companies & CNPJs

Cash Pay Meios de Pagamento LTDA — 48.689.840/0001-30

Golden Cat Processamento de Pagamento LTDA — 52.348.833/0001-41

YCF Shop / OMS Tecnologia LTDA — 46.558.143/0001-14

X. HAO LTDA — (same as Golden Cat CNPJ repeated)

This full report has been delivered to the relevant authorities.

Awareness, however, is one of the few defenses ordinary people have against criminals like Sun and Hao. Delete the message - and block the number. It might help starve the criminal machinery that depends on new victims to survive.

To find out more about @akaclandestine's work, visit his Twitter (X), or check out another Case Study:

"In a so-called 'safe space' for teens, @akaclandestine finds the adult in the room…"

Read:OSINT vs KidsChat: Who Owns the Web’s Oldest Predator Playground?

Start your free enterprise trial

Get Free TrialReveal what's behind any contact, instantly.

We want to hear your story!

Inspire Others

Educate about what OSINT can do.

Positive Publicity

Share your success with the world.

Support #OSINT4Good

Be part of the OSINT story.